Ian Emes: A retrospective to reflect now

One of These Days at Unit 24 Gallery is a retrospective of the career of Ian Emes, a pioneer of music videos and video art.

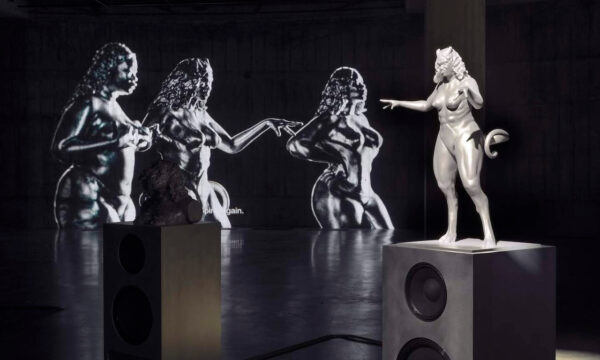

The opening on 1st March, combined projections of Emes’s animations, dim lighting and coloured spotlights. Original cells of some of the artist’s most famous works – from his early career, animating for the prolific live shows of Pink Floyd – filled the gallery, placed alongside hanging torches for close examination of the bold colours and dynamic shapes Emes is best known for. The exhibition also includes some more intimate insights, such as early preliminary sketches and notebooks.

In an interview for The Upcoming, Emes expressed his views on the relationship between art, filmmaking and commercial filmmaking: a fraught issue, which he clearly feels strongly about. This exhibition gives credence almost exclusively to his personal, truly felt, artistic works. One can see a great emphasis on the relationship of music and moving images in the selection of his work. In the colourful and atmospheric set-up of Unit 24, a kind of nostalgia for a lost time in music can be felt. An honest harkening back to a time when rock and roll was a true expression of selfhood, not a pre-packaged image.

Although Emes offers a personal view on how culture should define itself (or rather, avoid being falsely defined by society and the media), One Of These Days is far from preaching. It does not actively impose one idea, but rather seeks to perpetuate the value of freedom and honest creativity. Standing as a retrospective, it is nice to see an exhibition from an artist with strong affiliations to musicians, which maintains focus upon the artist. One of These Days is very much an examination of Emes’ work and a retrospective of his broad and influential career.

Unit 24 Gallery’s retrospective exhibition is perfectly timed, as Emes’ work examines the problem of freedom in society, flooded with self-effacing advertising and information overload. On the gallery’s website, One of These Days is described as “a walk through the internet” – this collection of Ian Emes’ work should be taken as an experience, rather than a prescription of a certain feeling, or a specific meaning. In this respect, the influence of music in Mr Emes’ work is the most palpable – image and sound are completely interwoven in a way that affects mood and influences emotive experience.

The Upcoming caught Ian Emes for an interview, minutes before the exciting opening of his retrospective exhibition, One of These Days at Unit 24 Gallery. The exhibition spans his career with Pink Floyd and is an examination of his most artistic works. The concept of individuality and freedom is central to Mr Emes’ work. It is clear how strongly he feels about this issue and the problems that today’s emerging artists are faced with.

On Unit 24’s website, you mention that you’re a rock and roll film-maker who sold out to commercial films. Do you think it’s possible to build a bridge between the two or is it important to keep them completely separate?

I think it’s very personal. Some people can disassociate themselves from the sell-out work, and then they can put themselves into another compartment for the more personal, artistic work. Other people find the area blurred and that their integrity becomes corrupted by doing the commercial work. For me, I’ve always hated doing commercial work. I love the craft, but I hate the content. So there has never been any confusion for me. I’ve always felt that the content means nothing at all, and it’s all for the practice of the craft. So I didn’t get confused; and with the money that I made from the commercials, I would then make a film of one of my own projects.

In terms of practicing the craft and experimentation in your art work, is this something that you would encourage in new, upcoming artists? Do you feel that there’s any such thing as good, or more worthwhile, experimentation?

I don’t think there’s any such thing as a bad experiment. Because the whole point about an experiment is that it’s not guaranteed to succeed. And, as we say, the price of experimentation is failure. For me, there’s not enough emphasis on the benefits of failure. Through the process of trial and error, you make many mistakes; and through learning from those mistakes, you’ll eventually have a success. I think there’s pretend experiment, or packaging a concept, which for me is the most appalling thing you could ever do to make a brand name attach to an experiment.

Do you think that art and music can help a culture to define itself?

Without being old fashioned, I think art has a duty to be a mirror on society and to reflect on it, without thinking about being successful. I think there’s a big emphasis on being famous. I don’t think an artist necessarily has to be the starving garret artist, but back in the Surrealist period, or the Cubist period, they weren’t setting out to be successful: they were tackling an idea. So my worry is that people are too busy becoming a success, and not spending enough time coming to terms with the thought processes in their work.

Do you think it’s more difficult for people to create this individual sense of themselves now, than it was when you started your career?

I think there’s more opportunity, but I also think there’s more self-consciousness about identity. I don’t want to make sweeping statements, but I feel that the younger generation are being bombarded, all the time, with what they should be like. How they should be and the brand associations with that. Whereas, in the 60s, rock music was inventing itself and was going on regardless of the marketing. During the time of the concept album, there were some big philosophical ideas going around, from Dark Side of the Moon to The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway, by Genesis. The concept albums had ideas in them, and now … I don’t think a big music label would really want a concept album. It would be too challenging, or too unlikely to sell. Because of the money, people control everything now; no one wants to take a risk.

There’s something about the experience of live music that can take you out of yourself. How do you think that music and moving images relate in this way? Do they create a relationship that feeds off each other?

I have to talk personally, because music was a big part of my life growing up and Pink Floyd, in particular, were an enormous influence. One of the reasons that they were so inspirational for me is that they have an architectural background. They went to architecture college and so I think their music creates spaces. It creates environments of sound and I was so stimulated that my mind would soar, and so I would see images that were stimulated by the music. As for the live experience, that was the most thrilling when Floyd started to use imagery in their concerts. The trick is not to force it on people, but rather to allow the music to stimulate their imagination and the visuals continuing this without over-defining. This makes it even more exciting and exhilarating because there’s part of you contributing to the process.

Could you perhaps say it’s encouraging an experience, rather than pushing a specific meaning or feeling?

Yes. And it’s also a group experience, a mass experience amongst your generation. It’s a generational experience. So you have ownership in it and it’s enormous, it’s as big as where your imagination can take you.

Finally, thinking about this idea of forming our own individuality, one that isn’t overly influenced by media and societal factors, does this exhibition offer your own subjective opinion on how that should be done, or just confront us with the issue?

Yes, it does. I don’t want to be preachy, obviously, but I’m playing with the idea of identity and with the notion that the corporations take the identity of youth and try to sell it back to them. For me, the worst thing is when a perfume manufacturer says “Be who you are, whatever”. Now, the thing about that is you can “be who you are” provided you buy my perfume. It’s an absolute abuse of freedom of thinking – to take the very concept of freedom of thinking, and attach a brand to it. And this is hitting on young people from every direction; it’s like rain, like static, it’s information overload. I would like to encourage young artists to listen to themselves, not care what anyone thinks and just go by their gut feeling. Not copycat, but just be stimulated and excited by something, and do what feels true to them. That’s what I want from the exhibition.

Abigail Moss

Photos: VJ Von Art

[slideshow]

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS