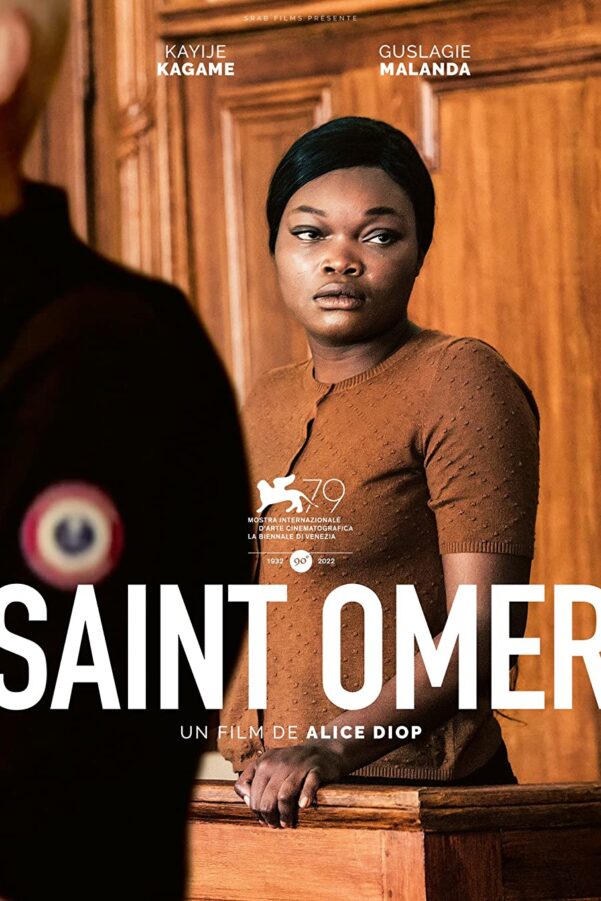

Saint Omer

Alice Diop’s career has thus far been concerned with the non-fiction storytelling medium of documentary filmmaking. Whether or not this has fed into her disposition as a feature filmmaker and reverberated through the walls of her hypnotic narrative feature debut, Saint Omer, is pure speculation. What is definite, however, after watching and processing the film, is that Diop has developed an extraordinarily unique cinematic language which communicates ideas about identity and motherhood with a dizzying heft, the weight of which is carried long after the theatre’s lights guide you to the exit.

Concerned throughout with the duality of identity, Saint Omer has two central characters who, while not directly paths or interacting in the traditional sense, mirror each other. A fiercely original use of the courtroom drama setup, the film takes place during the trial of Laurence Coly (Guslagie Malanga), a Senegalese immigrant accused of killing her 15-month-old child by leaving her on the beach to be swept up by the tide. A well-spoken woman of high education and with a detailed interest in the philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein (an interest which, during the trial, is ridiculed by her university professor who makes the absurd suggestion that she should pursue a philosophy with roots closer to her African heritage), Laurence presents the defence that she was under the influence of a curse, or some form of dark magic when she committed the heinous act, an act which she does not deny.

Rama (Kayije Kagame) is a writer and literary professor who travels to the commune of Saint-Omer in order to write a retelling of the Greek Medea myth through the lens of the highly publicised trial. Rama has virtually no dialogue, her identification with Laurence and her circumstances (she is in the early stages of her pregnancy, and, like, Laurence, has a fractious relationship with her Senegalese-French mother) are imparted to the viewer through glances, the subtlest shifts in demeanour which Kagame captures with effective nuance, and poetic filmmaking on the part of Diop.

Most of the film’s dialogue, in fact, comes from courtroom testimony which is unflinchingly depicted, the camera sometimes resting on Laurence in the dock for what seems like minutes at a time. Scenes outside the courtroom are mostly shot in forlorn silence, with the camera resting with equal patience on Rama in the depths of existential engagement in her Saint-Omer hotel room, save for a few reserved, yet pointedly revealing sections of discourse.

Diop is not afraid to test one’s patience. To be frank, it is a film that this writer was prepared to dislike, impatiently pondering: “Why do I need to watch Laurence’s uninterrupted testimony? Why do I need to watch Rama lying in silence on her bed for a whole minute?”, prepared to dismiss the proceedings as intangible film festival fodder. But Diop’s filmic vocabulary rewards patience and its slow, minimal editing reveals itself with time, the weight of its themes coming into focus so gradually that it leaves you not quite sure what you just experienced.

What you are sure about, however, is Diop’s ability to poetically project a lived experience through a lens which is almost mythical realism, in a film which is not designed to provide the answers, but to instigate the questions.

Matthew McMillan

Saint Omer does not have a UK release date yet.

Read more reviews and interviews from our London Film Festival 2022 coverage here.

For further information about the festival visit the official BFI website here.

Watch the trailer for Saint Omer here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS