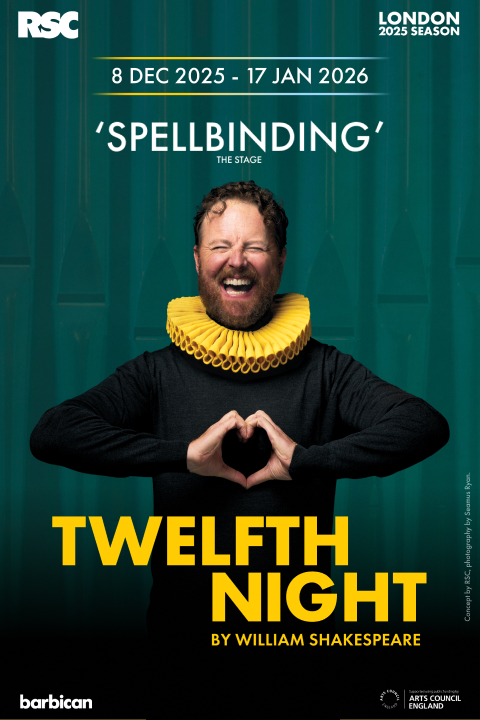

Twelfth Night at Barbican Theatre

As Feste, fool to the countess Olivia and fourth wall buster in chief of Shakespeare’s immortal farce of identity confusion, Michael Grady-Hall enters in about as extravagant a fashion as one would wish. A cable-bound crooner in a shock of pale face paint, Hall is suspended far above the stage to deliver a plaintive little tune (one of a handful provided by singer-songwriter Matt Maltese) before being promptly ordered away. It’s the kind of appetiser that stretches a production’s tone taut, braced for a comic release that, for the next 175 minutes (factoring in the intermission), will prove more elusive than may be expected of what’s been billed as a festive revival of a much-loved production of the Bard’s romantic comedy, the queerest and most oft-colourfully interpreted in his arsenal.

The first thing one may note is the absence of the aforementioned colour, in favour of the monochromatic, even severe pallor of James Cotterill’s set and costume design, with the majority of the cast decked out in the rigid formality of suits and ties. Such presentation may no doubt befit the station in which shipwrecked Viola (Gwyneth Keyworth) finds herself, adopting the guise of page boy Cesario to do the bidding of foolish, lovelorn Duke Orsino (Daniel Monks). What can be accounted for with less clarity is the sombre hush that hangs over Prasanna Puwanarajah’s production. As Feste – an alternatingly clownish and ghostly presence throughout – haunts the play’s fringes, singing his sad songs, one is left in little doubt that an exactingly specific aesthetic vision has been well and fully realised, with performers who never falter throughout. Still, one is often compelled to ask, not least in the especially stiff-backed first act of the new Twelfth Night, “To what purpose?”

Perhaps the intent is to de-emphasise the romantic foibles of Viola/Cesario, Orsino and the third party to their burgeoning affections, Olivia (Freema Agyeman), in favour of the drunken plotting of aptly named Sir Toby Belch (relished by Joplin Sibtain) to undermine and punish sourpuss steward Malvolio (Samuel West). If so, success. Sir Toby and his cohorts (Danielle Henry and Daniel Millar as, respectively, Maria and Fabian, while Demetri Goritsas approaches buffoonish Sir Andrew as a flop-sweat carnival barker) are so prominent as to eclipse the central trio altogether as the driving engine of this Twelfth Night. Keyworth and Monks are both able as our central romantic duo, but neither registers half so vividly – nor, seemingly, with anything approaching the frequency of – this quartet of schemers.

Still, Puwanarajah and co decline to revel in their triumph as so many others have. West’s Malvolio is a tough hang, stiff upper lipped and rigidly opposed to any Christmas revelry on Countess Olivia’s grounds. He also, in the actor’s understated interpretation, is no worse than your average humourless boss, and rarely has his humiliation and debasement seemed quite so pitifully sad. It’s not that we are forbidden to laugh at his yellow stockinged moment of downfall, but there is enough bleak gravity in the steward’s ultimate vow of revenge to suggest a kinship with the tortured souls of the Bard’s bloodiest tragedies.

In no way does this Twelfth Night seem unaware of this, but it suggests a thoroughly different show to the one described in the programme as a playful, boundary-defying refutation of the compulsory heterosexuality enforced by the ending of the play. One walks out soberly contemplating the justice in Malvolio’s punishment when it comes courtesy of the far better off Sir Toby, and what – if any – class critique Shakespeare may have embedded here. One thinks less on the interplay of affections between the central trio, though to the extent one does, it’s largely due to Agyeman. Forthright and funny, petulant yet sincere, hers is the production’s freshest performance, and the scenes shared between her and Keyworth’s disguised heroine are the only ones that ring with real tension of romantic possibility. When they both arrive at their happy endings, Puwanarajah’s production does not dispel or extinguish the implications of what has come before, as promised, but there is still little warmth to be found in spite of this. Instead, we conclude with Feste singing another of Maltese’s downcast ditties, closing things out on a note near-funereal in its solemnity. What exactly one is meant to feel at the end of it all is unclear.

Ultimately, this strange, tonally uncertain Twelfth Night leaves a haunting impression with the monochrome severity of its aesthetic and some strong performances. It also only half-registers as a comedy, and genuine romance is in scarcer supply yet. One applauds receiving so unexpected a subversion of the promised festive goods while still contemplating what the intended emotional effect of this approach may be.

Thomas Messner

Photos: Helen Murray

Twelfth Night is at Barbican Theatre from 8th December 2025 until 17th January 2026. For further information or to book, visit the theatre’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS