Ruin Lust at Tate Britain

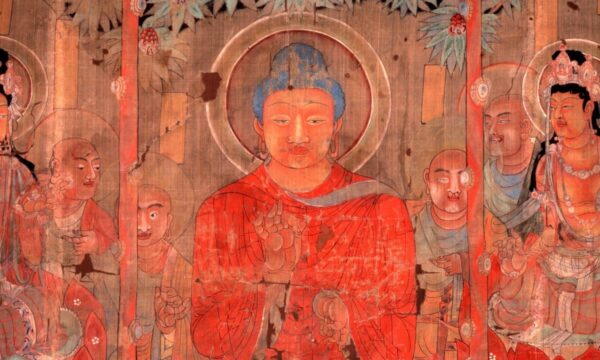

Featuring a range of artwork from the 17th century to the present day, from over 100 different artists, Ruin Lust, at the Tate Britain, is an exhibition that traces man’s continued fascination with decay and destruction.

Epitomising the 18th century obsession with ruins, is JMW Turner’s Tintern Abbey: The Crossing and Chancel, Looking Towards the East Window, 1794. Here a man-made structure is seen wrestling with the great forces of nature, as lush green vines seek to reclaim the twelfth-century Cistercian Abbey, while a group of amazed tourists look on. This romantic fascination with ruins, as wondrous relics of the past, was still prevalent in the academies a few decades later, as seen in John Constable’s Sketch for “Hadleigh”, 1828-9.

Revisiting this 18th century obsession with ruination, but in a satirical context, comes witty works from Keith Arnatt, Patrick Caulfield and John Latham, whose work Five Sisters Bing, 1976, presents a heap of post-industrial shale being transformed into a monument. For these later artists, ruination provides a means of ridiculing existing social structures and pompousness of the past.

In contrast, for the next group of artists, ruins are viewed as a sign of destruction. In Devastation, 1941: East End Street, 1941, Graham Sutherland represents the violence and brutality of WWII through an image of bombed buildings. Muddied blacks choke the faint outlines of a narrow street while a sombre yellow lends an overall haunting quality to the work. It is this sense of devastation that is felt in the war-torn works of John Piper, Jon Savage, and Jane and Louise Wilson.

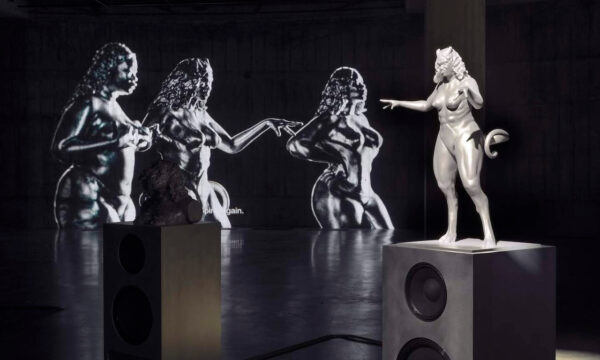

The exhibition also deals with ruination as an abstract theme. A room dedicated to Tacita Dean, shows Kodak 2006, a film installation that explores the ruin of images, as the technology of the 16mm film becomes superseded.

While a visually stunning documentation of man’s fascination with ruins, more could have been said on the individual periods, movements and artists featured. As is the case with many transhistorical exhibitions, there tends to be an emphasis on similarities as opposed to differences, and a tendency for sweeping generalisations as opposed to specifics. However, in terms of the sheer amount and variety of works featured, Ruin Lust is a must see.

The editorial unit

Photos: Rosie Yang

Ruin Lust is at Tate Britain from 4th March until 18th May 2014. For further information visit the gallery’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS