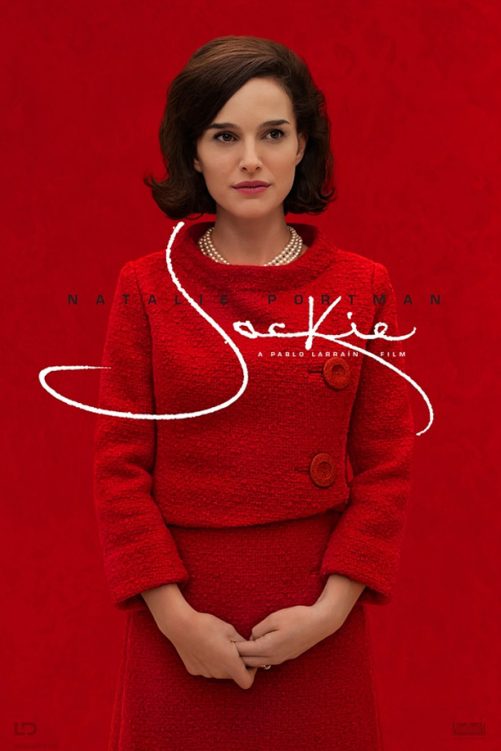

Jackie

When it was announced that Pablo Larraín – possibly Chile’s best working filmmaker, or at least its most prolific – would make his English language debut with a Jackie Kennedy biopic, there was the impression that his distinctive authorial voice would be suppressed in order to appease a homogenised Hollywood market. Jackie is therefore remarkable in that not only is it every bit a Pablo Larraín feature, but it is, in many ways, his most successful project to date; not so much a biopic as a swirling, provocative take on public and private narratives, on American iconography, and the inescapable insufficiency of cinema in attempting to sum up an individual’s life and legacy.

Jackie Kennedy is played by Natalie Portman, who certainly looks the part. And once Billy Crudup’s Life magazine journalist arrives at her residence in the aftermath of the assassination, we learn that she sounds the part, too. The breathy, deliberate accent takes some getting used to, but Portman internalises the role so well that such reservations are soon forgotten – thanks in part to Larraín’s technique. Rejecting the arms-length approach of some biopics, he elects to film largely in fluid, 16mm close-up, a raw examination of Jackie’s calculated but crumbling façade. Moments of public poise are undermined by powerful moments of vulnerability, such as the harrowing shot in which she wipes flecks of her husband’s skull off her face.

The director’s innovations spread to his structure, which takes several layers of narrative – a televised tour of the White House, the immediate aftermath of the assassination, a conversation with John Hurt’s priest – and cuts between them freely, connected by emotional rather than chronological links. This may seem unfocused in practice, but there is a certain cumulative power. Scenes place equal prominence on personality and legacy, and serve to remind us that while the Kennedy administration only lasted two years, it was definitive, thanks largely to Jackie’s influence, in publicising and glamorising the halls of power.

With all this talent flying around, then, it’s surprising to note that the star of the show is Mica Levi’s score. Essential in defining Under the Skin’s creepiness, she works on another level here, antagonising loud marine band soundscapes with her signature strings; it’s haunting and deeply personal, burrowing deep into a complex psychological mood.

Jackie concludes on the same note of Citizen Kane, in that, for all its efforts, a film can never sufficiently encapsulate an individual. Yet in a year in which the White House has somewhat lost its lustre, a feature like this is essential viewing – not only to remind us of the power of those at the top, but also of their inherent vulnerability, and the enormous effect that even their smallest actions can have.

Filippo L’Astorina, the Editor

Jackie does not have a UK release date yet.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS