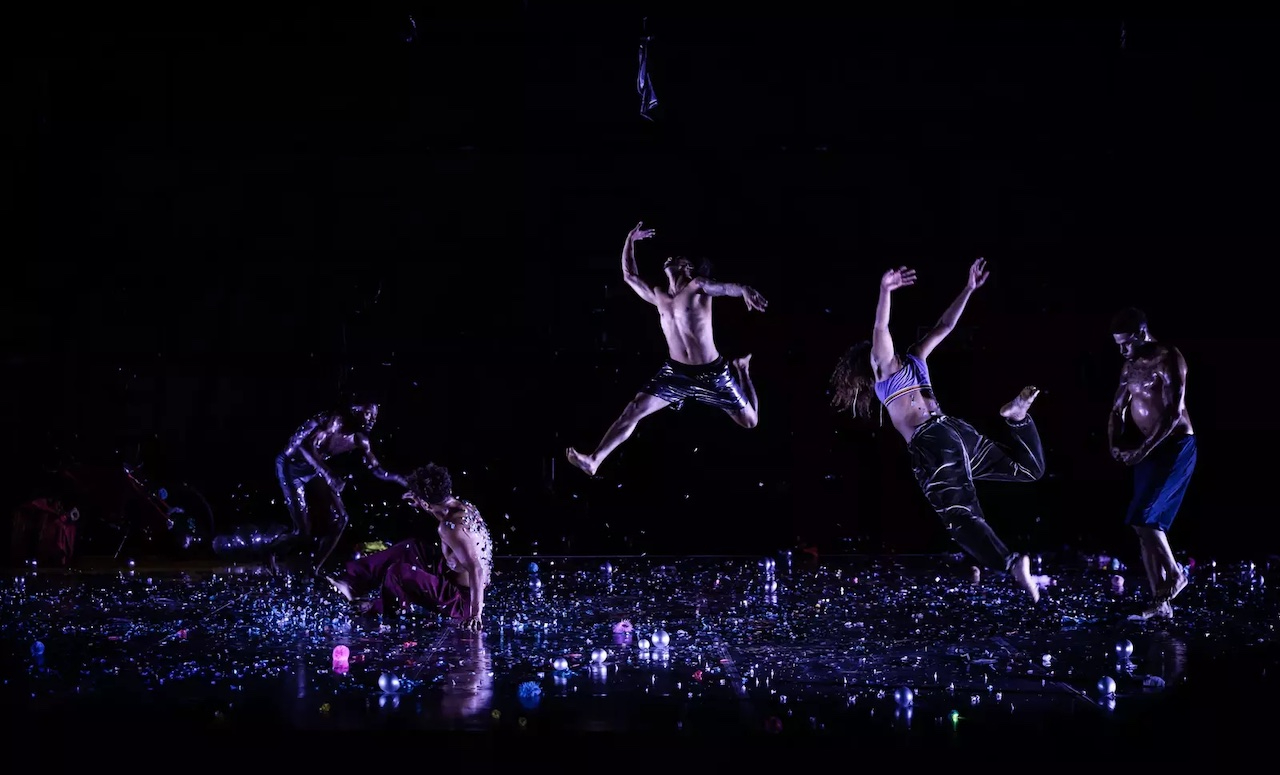

“I look for a space where the dancers and I can find freedom to create and to express without judgement”: Alice Ripoll on Zona Franca at Southbank Centre

Since 2009, Alice Ripoll has been combining improvisation, contemporary dance, dance theatre and a range of movements inspired by Brazilian genres, to explore movement and the human experience. Initially training as a psychoanalyst, Ripoll explores unconscious processes that are channelled through her company and allows the movements to unfold for the viewer to take away what they will. Her new piece, Zona Franca, was initially born during the end of lockdown and evolved against the backdrop of the political fall of the right-wing dictator Jair Bolsonaro. Using a range of movements, from contact improvisation to Afro-house and TikTok-inspired choreography, Zona Franca offers a unique avant-garde perspective on Brazil’s changing circumstances. We spoke to Ripoll to find out more about her process as a choreographer and what to expect from her upcoming piece.

Can you explain the meaning behind the title Zona Franca?

Zona Franca is an expression in Portuguese, which means “free zone”. It’s about the way I look for freedom in my creations. Every time, with a new creation, I look for a space where the dancers and I can find freedom to create and to express without judgement, without external and internal censorship. The dancers in this project are much younger than me. They are from a different generation. For example, with the internet, very often they would bring me a step and I would say: “Where did you take this? Who is the author?” They would say it’s from the internet, where everybody shares everything. I think the language they bring, it’s very connected to freedom.

Could you tell me a bit about how the theme of crossroads is explored in your piece?

The beginning of this project was hard because we were facing the end of COVID-19 in Brazil, which went on much longer than in Europe. We were still in the last month of the Bolsonaro government, having elections. It was very difficult to work and to concentrate on anything else. It was months where the country literally stopped; it was the only thing anyone could talk about. That was the context we started from. A lot of things in culture happened in Brazil, a lot of things were destroyed. It was like a crossroads in our lives. What would be the future of our group? Would we be able to continue? It was in the room, you know?

How are collective settings explored in this piece?

It was about the question of: what is the relationship between one individual and their community? It was a bit of a parallel of what we’re facing as a society and as a community in Brazil. How strong is the community to put somebody like Bolsonaro into government and how strong are we as individuals to fight against it? How does this collective decision of choosing this president affect us individually or as a group? As a dance group, we were in a special moment: we were a ten-year-old group and some people couldn’t stay because of personal reasons. So we had to question if we should invite new people into the group and how that would change the atmosphere or not. When you are already ten years old, as in any relationship, how do you look for new things? These kinds of things that were very part of our structure, ended up becoming a theme that we would address in terms of the piece. What do we keep? What do we let go of?

So the crossroads theme refers both to the crossroads that Brazil was facing, and the crossroads that your dance company was also facing?

Exactly. Because we met in a specific context. I work with contemporary dance, and I was invited from a festival in Brazil, to create a piece. And then we did our first creation, which was completely based on an urban style of dance called passinho, and so was the second one, so for the third I said: “Okay, we have to go somewhere else, you have to open yourselves. We cannot do a third piece about passinho. You have to reinvent yourself as professionals and as dancers.”

How would you describe the type of dance that’s used in Zona Franca? And how has it evolved from what have done previously?

The company brought me new kinds of dances that they had researched. Dances that are connected to Afro dances now have new styles that mix the beat of Brazilian urban dance and Afro dances. I don’t really go into this, I just work with what they bring to me, on how to create the universe to put these kinds of dances and choreographies in. In Brazil, it’s so crazy: every summer we have a new dance – and there are a lot of people who are very creative. Dance is very strong in Brazil, popular dance, urban dance – and so new techniques go together with a new kind of music style, a new rhythm that the DJs would invent very differently each year.

How would you describe the type of dance that’s used in this piece?

I would say maybe dance theatre. Normally people would call my kind of work contemporary dance. But for me, I prefer the phrase dance theatre because I’m very interested in addressing the work of art that we do in a more open way, so everything that happens in the rehearsal room. Other subjects would appear in this context, so I’m creating the piece also with the things that are not in the piece and not the centre of what we are looking for. I also work with texts, with voice and with improvisations that are more in the theatrical field.

It sounds like it’s quite a collaborative environment in your company.

It’s very collaborative. I never know where we’re going to go. I prefer to start completely white. Like white paper, where we can write everything on it. And so we start from zero. We don’t have an idea or subject that we want to address. It’s improvisation. There is sometimes a scene or a movement that I bring, like, “Oh, I pictured this. Now you’re doing this choreography.” But it’s kind of like a blank canvas where things start to appear. We have a lot of tools for improvisation exercises. And then people come in and start kind of playing around, and then you see what comes out of it. The images only start to appear for me after the company brings me something. So it’s very collective.

With the performance you’re currently working on, what were some of the moments that shaped what the show became?

I have a son who is seven. And once during the process, I was at a children’s party with him. And there was this pinata. The image was so strong because when they finally hit the pinata and all the small things fell out on the floor, the children started acting like animals. It was such a strong image because some of them would leave crying because they could not get everything. And then they start fighting over the things. It’s like the parents trying to show them: “Okay, your life in capitalism is made to be something like this.” I thought it had to do with what we were addressing: fighting for survival, the cruel aspects of the last big event that we had experienced. So I brought it to rehearsal, we used balloons, we put things inside. And there were specific moments where they would hit and hit.

How much does Brazilian politics feature in this piece?

I think it’s there. Because in the moment we were in, it wasn’t possible to create something where politics was not there. It’s not something that when you watch the piece, you will recognise very literally. But you can feel the heavy atmosphere, the violent atmosphere.

What would you say is the central theme of Zona Franca that you’re trying to get across?

I don’t think there is a message. That’s not the way that I like to work. I work more with themes. There is a kind of dance that is very close, in my opinion, to journalism or to sociology in these aspects, where you have a theme that you can recognise, and you can get a message from it, but I don’t like to work like that, I like to work in a more open way. I prefer to work like that because, very often, I still don’t know very much about what the piece is about, which can be dangerous because you don’t know exactly where you’re going. I work a lot with images: “This image is strong,” we keep it, and I don’t justify to myself or to the dancers why it is strong. I try not to give explicit explanations to the dancers. I prefer to take the piece as sensations, images that are open, really open, and the people will make the connections.

What inspires you as a choreographer?

People. I’m very interested in people and looking at the way they move, the way they live and the way they talk. It’s very much about connecting, connecting to people, and then trying to find a way of expressing and communicating together, even if we don’t know what we are doing. I always think that if I had a different crew in the creative process, the piece would never be the same. It’s very much a listening process. You’re listening to what people are trying to express. I think it comes very much from people that are close to me. I like to say I have to be in love with them – not with all of them because sometimes it’s not possible. Sometimes it’s with one of them that represents all, but it has to be passionate. Otherwise, the thing doesn’t flow. It’s relational. But it’s not that I go into their personal lives. I don’t like to bring up your experiences. Tell me about your life. Tell me about your childhood. It’s not like that.

The more important question for me is: what makes a movement expressive? Why it is expressive? It makes you feel like you cannot stop watching because there is an expression happening there. When you’re talking about dance, you don’t go about what is being expressed, because you don’t put it into words, it’s movement. But even if it’s moving, there is the expressive aspect. And then, for the dancers to be open at this point, not only to do choreography but also to express sensations through the body. It’s a trust process, they have to trust me. It’s personal, but it’s not at the same time, because when I am there as a choreographer, I am me but at the same time, I am representing the audience. We’re trying to do something big. So we are a bit like channels, the thing that things have to pass through. So it’s abstract, but it’s personal, but it’s not only personal.

I think it’s the unconscious. So when you touch it, it’s an unconscious kind of thing that’s being expressed that you’re both witness to, but you don’t necessarily have conscious words for it because it’s unconscious. It’s something transpersonal. Or there is an aspect of it. There is a collective.

What got you interested in choreography?

I didn’t take a common path, I didn’t start in the art field, I was doing psychology at university. And then I started to learn some psychological techniques that use the body. And then I started to look for some kind of technique to move my body and I ended up going to school in Riol, which is very interesting because it’s a cool school, both to study dance and to learn how to work with people who have disabilities. I think it was an excuse already because I think I was always interested in the art field, much more than the academic.

Sophia Moss

Image: Renato Mangolin

Alice Ripoll: Zona Franca is at Southbank Centre from 2nd until 4th November 2023. For further information or to book visit the theatre’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS