The Handmaid’s Tale at the English National Opera

In the face of significant turmoil and internal conflict, the English National Opera has unveiled a revival of The Handmaid’s Tale, an operatic tour de force drawn from Danish composer Poul Ruder’s adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s iconic work. Despite the recent loss of its significant Arts Council England funding and a looming relocation mandate, ENO has, against all odds, staged a production of considerable merit.

Margaret Atwood’s dystopian vision, penned during the Reagan era, reimagines a United States fallen into the clutches of a despotic theocracy, following a nuclear disaster, where women, the handmaids, are coerced into childbearing servitude to perpetuate the ruling class. This prophecy is certainly prescient of today’s contemporary fears of environmental catastrophe and religious extremism.

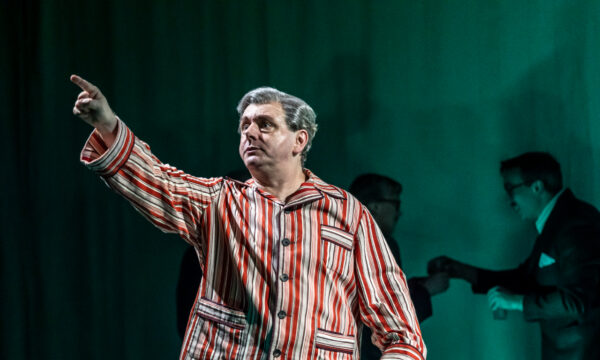

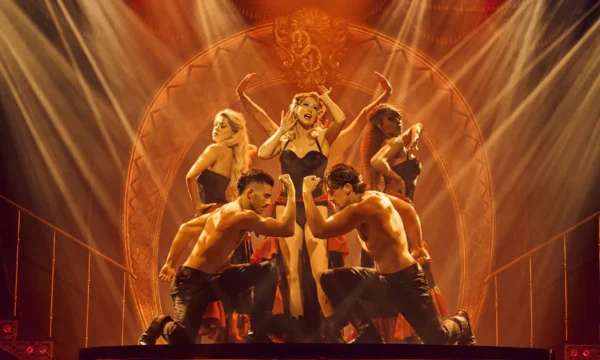

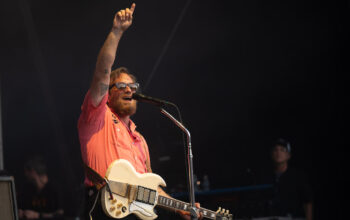

Under James Hurley’s direction, this adaptation is both challenging and gripping. The narrative unfolds through the diary of Offred, a handmaid portrayed with remarkable vocal and physical endurance by soprano Kate Lindsey. Her voice navigates the demanding score with an agility that belies the complexity of the music, delivering moments of haunting beauty even as she captures the very essence of agony. Avery Amereau stands out as Serena Joy, the sterile wife compelled to procure a sequence of handmaids for her spouse, the Commander, as surrogates for childbearing. Lindsey brings a rich contralto range to the fore, her timbre velvety and laden with sorrow, envy and despair.

This opera is not a frivolous diversion; it is rather more of a cerebral, cinematic journey. The score is layered with an unsettling mixture of liturgical influences – gospel, chant, hymns, and even Bach – and modern dissonances, which may prove disquieting to the ear, yet remains at points intensely magnetic. There are moments of profound musical depth, interspersed with segments where the score becomes tediously atonal. The unrelentingly high pitches can tax both the vocalists and the assembly. At intervals, the singing seems lifeless, flat – possibly an intentional representation of the handmaids’ bleak and hollow existence.

The orchestra, under the baton of Maestra Joana Carneiro, deserves recognition. Modernist compositions demand an attentiveness, a persistent count. The players seem perched on the edge, keenly focused on their conductor, executing each note and complex rhythm with extraordinary precision.

The actress Juliet Stevenson frames the performance with a monologue that establishes the context and introduces Offred’s tale during a symposium set in the year 2195 in the Republic of Gilead (formerly the United States), presided over by Professor Pieixoto. In this speaking role, Stevenson appears somewhat perplexed by her own presence. One almost wishes the production could stop with Offrey’s final climactic cry – a fleeting instant where the audience is granted a true, opulent crescendo.

Annemarie Wood’s set design starkly conveys the anonymity and oppression of Gilead’s rule. The rear wall of the stage becomes a chilling exhibit of the fallen, serving as visual coercion towards obedience. The stage is bordered by towering curtains, transforming the space into a claustrophobic arena of despotism. A half-curtain descends partway through the stage, bringing a heightened focus to the more intimate moments of the show – this curtain also becomes a canvas for grayscale videos that flicker through memories of The Time Before – highlighting the contrast between Offred’s previous life of feminist awakening and her current plight.

The Handmaid’s Tale at the English National Opera is not an excursion for the faint of heart. It is a brooding, introspective affair that leaves one ruminating on the precarious state of democracy – and the uncertain fate of ENO itself.

Constance Ayrton

Images: Zoe Martin

The Handmaid’s Tale is at the English National Opera from 8th until 15th February 2024. For further information or to book visit the theatre’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS