“Every time I work with Gareth, I learn more about storytelling through action and action through storytelling”: Jude Poyer on Havoc

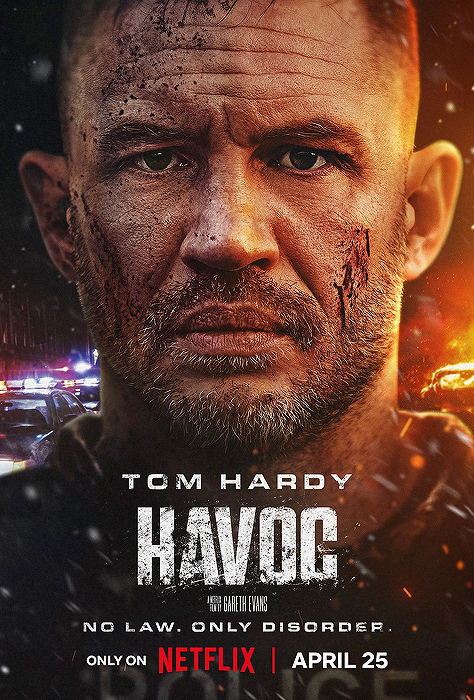

An absolute powerhouse of an action film, Gareth Evans’s Havoc fuses the world of old-school Hong Kong movies by the likes of Ringo Lam and Johnny Woo with the aesthetics of American crime cinema. It follows Patrick Walker, a disgraced police detective, trying to detach himself from the corrupt politician Lawrence Beaumont, played by Forest Whitaker. With one last task at hand, before he can finally turn his life around, Walker must save Lawrence’s estranged son Charlie after a drug deal goes wrong. Now he faces a Chinese triad and several traitorous police officers hunting him down. Boasting intricate fight sequences that blend mixed martial arts with gunslinging prowess, Havoc doesn’t sacrifice good storytelling and detailed character-building for the sake of thrill and excitement. Instead, it carefully weaves psychology and emotional beats into the choreography.

For a feature like Havoc to work, a lot goes into envisioning the stunts to ensure that everything flows seamlessly. As Evans stated in our interview with him at the red carpet premiere of Havoc, they scrutinised every little detail to find ways to use these physical scenes to relay plot and character work into the story. One of the key people behind the fantastic production of Havoc is stunt coordinator and action designer Jude Poyer. He has worked with Evans on the picture Apostle and in the TV series Gangs of London. With similar affinities to the director in terms of Hong Kong bloodshed films, Poyer knew about the project even before Evans finalised a script. The Upcoming caught up with the stunt coordinator to talk about his work on Havoc, the collaboration process with Evans and the importance of telling stories through action.

To start us off, can you give us an introduction to the film and what people can expect from it?

Havoc is not your typical action movie. It’s a movie that, in many ways, pays homage to the classic Hong Kong heroic bloodshed films of the late 80s and early 90s – the films of Ringo Lam, John Woo and Johnnie To. But it’s also inspired by filmmakers like William Friedkin and Paul Verhoeven. It’s a movie with depth; it’s a movie that stands on its own. Obviously, I’m the stunt coordinator and I’m involved in the action design. But what Havoc has is a lot of heart and a lot of nuance. I hope people go in with an open mind, expecting a thrill ride and they’ll feel something by the end of it.

You talk about yourself being the stunt coordinator and being in charge of designing the action. For anybody unfamiliar with the work, can you explain what that role entails?

There are kind of like two sides to being the stunt coordinator. One of them is the aesthetic side: choreography, coming up with ideas of what might be exciting, what might look good, and what services the story and the characters. But there’s also the technical side: how do we do it safely, how do we do it so that it’s believable? So, it’s technical and artistic. I love working with Gareth because Gareth is definitely the best director of action working in the West, and one of the best working in the world. He has a great appreciation, encyclopaedic knowledge and understanding of action sequences and action cinema, and we have very similar tastes and references. We work very comfortably together because we can explore ideas. For example, we look at a movie like John Woo’s Hard Boiled and go, “Okay, how do we add a little bit of flavour to this?” But it’s not simply imitation because Gareth has his own voice and he presents action his own way. Stunt coordination, fight choreography – most of it is 50% physical performance. What really matters is how to present it on the screen: how it’s photographed and how it’s edited. Gareth is an innovator in that. We take our inspiration from Sammo Hung, Jackie Chan and John Woo. But John Woo took his inspiration from Sam Peckinpah, and Jackie Chan took his inspiration from Buster Keaton. What Gareth does is he doesn’t imitate, he gets inspired, and he has his own voice and his own style, and I see people trying to imitate that.

Aside from Gareth, when you first encountered the script, what made you want to be involved in the project? What was it about the story that drew you in and what parts of it did you feel like you could do some magic with?

Gareth was a big part of the attraction because I worked with him on two projects before, and I absolutely love working with him. Every experience is creatively very satisfying and very fun. He creates a very healthy and happy environment in which we do things that look very violent and dangerous, but it’s not that at all. I knew about Havoc before there was a script. Gareth and I talked through his story and his characters while he was writing it, and we talked about our reference points. Because he wanted to do something that was in many ways a homage to those classic Hong Kong films that made me super excited. I was excited to work with Gareth again, but also – I’m a Hong Kong film fan. I started my career as a stunt performer in Hong Kong, and I was there for eight years. Gareth, in Havoc, created a canvas where I could lean into my Hong Kong background and my Hong Kong inspirations. We were able to do things in terms of choreography which would not have worked in a different setting and a different world. It wouldn’t have been right for Gangs of London, for instance. We have a Chinese criminal gang in this, so we can do certain types of choreography that are right for that world and that lean into the Hong Kong aspect. I was able to bring in stunt performers from Hong Kong to work in these sequences, and they are among the best in the world. They just bring in a certain flavour, work ethic and talent, which is very evident in the finished movie. One of the Hong Kong-inspired things was the Assassin character played by Michelle Waterson-Gomez. Michelle is someone I’ve wanted to work with for almost ten years, ever since I first saw her fighting in MMA. She has amazing charisma and beautiful technique, and she’s tough as nails! I thought she belonged on the screen, so I was able to propose to Gareth having a character that Michelle could play. When we would choreograph those fights, it was always with Michelle in mind. For me, the movie is not like a Hong Kong movie; this is a movie that stands on its own. But having a henchwoman character that’s pretty much silent, and then she turns up and she absolutely presents a huge physical challenge to the protagonist, that harks back to the great Hong Kong films of Jackie Chan, Sammo Hung and Jet Li from the 90s.

And what’s your working relationship with Gareth like? How open is he to the ideas you propose, and were there any discrepancies when it came to the creative side of building the action?

When we work together, it’s a very collaborative environment. We first worked together on Apostle, which is a horror, and had a little bit of fighting, but not a lot. It was a very comfortable experience. Then we did Gangs of London – it was myself, Gareth and, I think, four stunt performers. Gareth is a world-renowned, world-respected director who has made, with the Raid movies, two of the best action films ever made. But he’s incredibly down-to-earth, incredibly humble, and very collaborative. When we work together in that environment, there is no hierarchy. In reality, he’s my boss, and I’m the boss of the stunt team. But all ideas are received and all ideas are interrogated. If I have a choreography idea and one of my stuntmen or stuntwomen says, “Actually, I don’t believe that,” or, “Wouldn’t this be better,” we examine it, and there’s no ego. It’s all in service of the project, and Gareth helps to create that environment. That’s really the only way I want to work is when there’s no sense of hierarchy during the design. We previs everything; everything is shot and edited meticulously by Gareth before we start filming. The stunt team and Gareth will act out all of the fights in a gym or a studio – we built that nightclub and that fishing shack out of cardboard boxes and plastic tubes – so Gareth knows exactly what he wants. When we step on the set, what we like to say is, at that moment, “I’m not the boss, Gareth’s not the boss, the previs is the boss.” We serve that previs and we follow that previs meticulously. You don’t get that intricate action like in Havoc unless you fully interrogate on a granular level, shot-by-shot, what you want the audience to see.

There are a lot of amazing characters here, a lot of stories with so much action and thrill. Havoc is chaotic in that sense, which is why it’s called Havoc. You talk about your job in two parts, with one serving the aesthetics and the storytelling. Was it difficult to try and balance all of that while making sure the audience doesn’t get too lost in the action and lose the heart of it?

That’s not really my problem; that’s something Gareth, his producers and editors consider. I’m more across the action sequences and just making sure everything rings true from the story and character point of view. It would be strange if Forest Whitaker suddenly threw a jump-spinning backkick in the middle of the fight sequence when you know he’s meant to be an older gentleman who’s a politician. Gareth would never propose something like that, but that’s the kind of integrity I try to focus on. Because Gareth is so collaborative, we can talk character and story, and sometimes we’ll even suggest losing bits of action. Maybe a certain beat we really like or a choreography idea or a stunt looks good in isolation, but as part of a bigger tapestry, it doesn’t serve it. But Gareth has worked really, really hard to craft a movie which works emotionally, dramatically and narratively, as well as from an action point of view. Talking specifically on the action, one of the things that Gareth is pretty good at, which other directors aren’t good at, is he establishes geography. Before a sequence happens, he lets the audience be familiar with the layout of the place. Once you get into the nightclub, it’s going crazy and there are three or four different fights going on in different places, the audience isn’t lost. I’ve been in this industry for 30 years now, and I’ve worked with a lot of directors and a lot of the best action directors. I have to say, every time I work with Gareth, I learn more about storytelling through action and action through storytelling.

You also worked with Tom Hardy in this film. He’s the quintessential anti-hero. Tell us about your experience working with the actor, and specifically what he added to these sequences that you’ve created.

One of the things that’s good about Tom is he brings sincerity to his performance; you don’t feel like he’s phoning it in. Some actors aren’t that invested in their performances, or they sometimes don’t care that much about the action sequences. It’s just one of those boxes that need to be ticked. But Tom interrogates the previs, interrogates the choreography, and thinks about how it sits with the character and how he will perform it. When he does it, he wants it to be convincing. It helps a lot that because of his interest in martial arts and jiu-jitsu, he wants it to come across in a convincing manner. It also helps a lot that he has a very talented stunt double that he works with a lot called Jacob Tomuri. Jacob’s been with him since Mad Max; they could be twins to look at, and they have a great working relationship. Also, Tom probably enjoyed fighting Michelle an awful lot because of Tom’s passion for jiu-jitsu. He had great respect for Michelle, and by the time it came to shooting that fight scene, even though they looked like they were really trying to hurt each other – which is how a fight scene should look and feel – there was respect, trust and familiarity. This meant that it was a pretty straightforward and comfortable process. Not always comfortable in a physical sense from Jacob, because he took some very hard hits from Michelle, and Michelle took some too. But it was a pleasure working on that fight with them.

Finally, you filmed in Wales, but you’re trying to build this Americanised city. Did that aspect of it make your job in designing the action harder in any way?

It didn’t make my job harder. I didn’t have to worry about set dressing unless it had to do with facilitating stunts, and I didn’t have to worry about which side of the steering wheel the cars were on. The production designer, the art department – it was very much on their mind. The visual effects team had done a really great job with it, too. I actually have a home in Swanse,a so it was actually really nice to go to locations which were like ten minutes from my home. From a purely selfish point of view, I loved working in Wales. Hats off to the art department, the visual effects team and Gareth for that attention to detail. I don’t think anybody would believe this movie was shot in Cardiff, Swansea or Newport, but I’m sure residents in that area will recognise it. I think what they’ve created is a nondescript but very convincing American city. On top of that, because I’m someone who lived in Hong Kong and consumes a lot of Hong Kong movies, I think one thing we also got right was conveying that triad culture and the criminal world aspect with integrity and respect. Sometimes, I see movies where they don’t quite get it right, and I hear people who can’t speak Cantonese mangling it because they’ve learned it phonetically. That was even something we brought into the sound design. Even in post-production, Gareth and I had people from Hong Kong come in and do voice work, native speakers using the right kind of tones and language that those people from that world would use.

Mae Trumata

Havoc is released on Netflix on 25th April 2025.

Watch the trailer for Havoc here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS