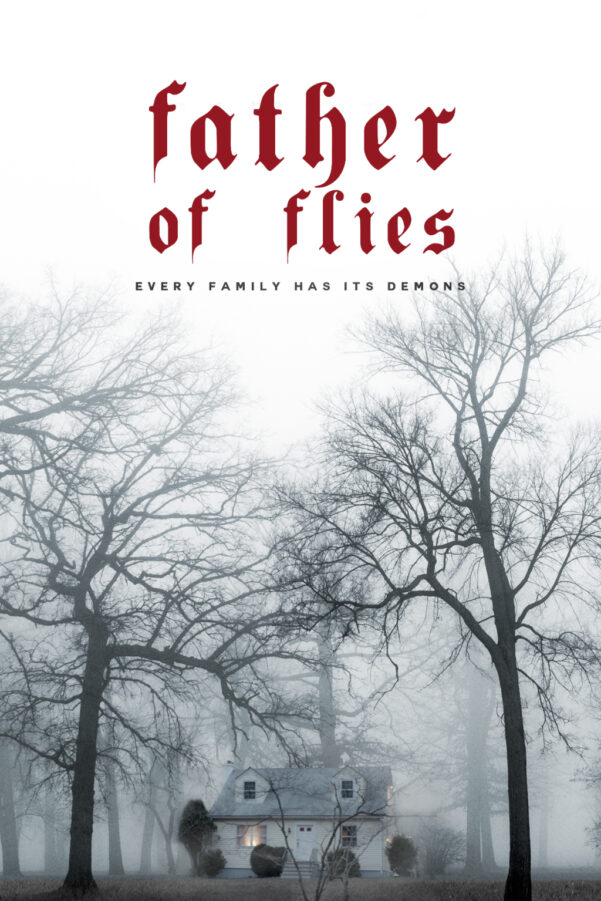

More than just a few jump scares: Ben Charles Edwards on psychological horror Father of Flies

Father of Flies is the new psychological horror from director, writer and producer Ben Charles Edwards. Born out of the personal traumas the filmmaker suffered growing up – his parents’ divorce, living in what he believed to be a haunted house – the movie follows a young boy who finds his mother forced out of the family home and replaced by a mysterious new woman. Seemingly also arriving with her are unsettling supernatural forces. Made during the pandemic, the film almost didn’t make it to completion but, after the sad passing of one of the lead cast, Nicolas Tucci, Edwards was determined to see its conclusion in honour of the late actor.

The Upcoming had the honour of chatting to Edwards during the Raindance Film Festival about the inspiration behind the film, how he sees it sitting within the horror genre and the numerous other projects he’s completed during lockdown, including producing A Bird Flew In and documentary Quant, directed by Sadie Frost.

Hi Ben, such a pleasure to be able to speak to you. By way of introduction, can you tell us what people can expect from Father of Flies?

Well, I don’t know. I’d say I hope that they enjoy it, find it scary… I’ve always loved horror; I don’t particularly love the trashy gory ones, where a cheerleader gets stabbed or whatever – that’s a preference. But I had a long chat with a guy called Dominic Wells who is this big journalist – he is a great guy – he was the editor of Timeout for many years, I think he’s at The Times now, but we had dinner one night, and he told me, “So Ben, just write about something you know, just try and make something you can connect to in some way.” And I thought, “Well, how can I do that with a horror?”. Growing up, I genuinely believe – as stupid as it sounds – I did grow up in a haunted house. And I had all these memories and things that happened to me and things I saw in my room and all sorts of stuff. So in that sense, I think that’s why I’ve always had an interest in it. But at the same time, the story is about families going through divorce and the emotions that that brings, and how fragile and delicate our families can be. And that anxiety, the underlining anxiety that sits there, throughout those kinds of transforming processes of mum moving out and dad moving out – the same happens in bereavement, with grief – it’s the transition. And when things transition, there’s an underlying anxiety; there’s, “Well, what’s around the corner?”. And when you team that with a haunted house, or something paranormal that could potentially be going on, it’s quite an exciting thing, the stakes feel quite high. That being said, it also creates a platform for a film to hopefully actually dig a bit deeper into the emotional state of this family. And I think, from the reactions and the reviews we’ve had so far, hopefully – you never know – that element of its been a success. Rather than just seeing everyone jump, in some of the test screens I quite enjoyed making everyone cry! You know, you go to see a film for that roller coaster – or I do, that’s why I enjoy horrors, especially the good ones. I want to sit there and lose my breath at times and to feel stuff – and nothing for me does it as much as a good horror. Horrors rely a lot on the score, don’t they? And I’m really happy with these composers, this guy called Gus Collins: he did such a great job and I think it’s just elevated it, hopefully for that emotive level where the audience is going to feel something a little more than just a few jump scares.

How did you translate some of the feelings you had as a child and carve them into a narrative, with some of the things that were in your imagination manifested?

Really good question. I think life has very similar tropes to horror films at times. That’s why horror is so effective. We don’t try to be overly smart with fear: there are innate fears, then there are reasons for those fears. Why do we get scared that something’s under the bed? Well, we’re the most vulnerable when we’re sleeping. You’re still, the room’s quiet and you’re sleeping on top of this gaping void below you, where anything could be lurking. So there are those traits and I think that’s an important thing to bear in mind. But also the main crux or the main backbone of Father of the Flies is this stepmother, this new entity in the house. When you think of what a mum is, a mother figure, she is your nurture, your safeguard, your place to go to when all else may be lost, and when you’re scared. What if mum isn’t there? What if it’s filled with this stranger, this person, this step-mum. “So this is my mum but she’s not?” – that’s where these traditions of the evil stepmother come from… mirror-gazing and this vanity. I was brought up by my stepmother, and it’s very natural for a child to villainise another woman that isn’t their mum – very natural. And it’s a stage that one has to work through, that for a big chunk of your childhood, this stranger in your house, that’s winning your father’s affection becomes this – it’s an unknown entity. And you’re meant to just be close to this person. It’s a strange dynamic, isn’t it, when you think about it? And we’re very quick to villainise people. It’s an obsession of mine, this ambiguity of good and evil, and then how and why we villainise some people, why some people are happy to play the villain and why some people have to play the victim. And my stepmother, bless her, I love her very much – but she was quite happy to play the villain because she probably realised this is what we needed. It was a cathartic process for us. So, you know, I think we owe her a lot for that. So that’s where it seemed golden in my mind: the evil stepmother is such a nice trope for a horror film. So that was the start of it really. And let’s think twice before we villainise perhaps the wrong person – and that’s something, if you’ve seen the movie. That’s kind of the outcome. Do we really know who’s in our life, who is the danger around us?

Would you say you tap into certain tropes, like the house itself becoming a character or some of the visual images, such as the step-mum with her face mask? To what extent do you take inspiration from other films? Where would you say your film sits in the genre?

You know, I think inspiration and ripping off is a fine line, I really do, and I actually think the more bold and obvious you are with “this is my reference”, the better, because I’m saying basically, “I love this and I’m paying homage to that”. And that’s a nice thing to do, because, I mean, my god, if one day someone did that to my film I’d be very happy! If you’re disguising it, and if you’re just taking, that’s different. So there are certainly very obvious tropes within Father of Flies that you’d say, “Well, that director clearly likes Poltergeist” – there are clear references. So that’s one part of the inspiration. And then this mask… you know, I love masks. I’ve been obsessed with them since I was a child, and I enjoy the fact that when we have a mask on or even when I’ve got my reading glasses on, I feel like I can be more open. There’s an interesting thing, I think it was Oscar Wilde that said, “Give a man the mask and he’ll tell you the truth” – what a great quote and it’s so true. However, again, with the stepmother wearing this mask, it had parallels to the Wicked Witch mirror-gazing, the vanity that comes with these kinds of characters. Also, I remember my stepmother wearing a mask when I was a child. And I used to think, “My god, I barely know you as it is, let alone now I can’t even see your face.” So it creates this other barrier, and it’s an interesting point of conversation. In some ways, I do think we are more open when we don’t reveal our entire selves, and at the same time, yes, the opposite can happen as well – strange. But it’s a fascination of mine. So yeah, masks were an important part of it. I remember seeing Poltergeist as a child and just loving it, thinking it was such a cool way to create a portal. And there is something fascinating about static on a television because it really is like nothingness. Poltergeist seemed to make a lot of sense to me as a kid, that you could travel into other dimensions through a television screen!

Can you tell us a bit about your casting process? And of course the tragic, early passing of Nicolas Tucci? It must have also been fantastic to have had the chance to work with him.

Camilla Roberts, who plays the stepmother, is English and she’s a friend of mine here in London. So she came over to New York with me to shoot it, and I loved the idea of the stepmother being from another place as well. It further distances this alien feel to the children, these American kids with this British mother, stiff upper lip. I think Donna even refers to her as a “fucked-up Mary Poppins” in one of the scenes! I thought that was just quite funny as well. I wanted somebody that wasn’t American to play the step-mum and Camilla really fit the bill. And I think she’s a fantastic actress and does such a good job. And because of the twists and turns in the story, you needed someone that can play this kind of ambiguous nothingness at times; she worked really hard to leave the audience this open thing, “Well, what the hell is this woman thinking? Is she insane? Is it the British stiff upper lip?”. So that was really important to me. Nicolas Tucci, I loved him in You’re Next. So I saw that and thought, “Oh my god, he’s really cool,” and got in touch with him and he really liked the script, and we spoke for a few weeks on and off and he agreed to do it. I know people always say it about the dead, but he really was a fantastic guy. He really was. I really, really enjoyed working with him, he was just so cool. And he really got it and he gave so much. He was always the first on set and he was always the last to leave, even when he didn’t have another scene. He’d be hanging around and watching it. And I imagine he may have been sick at that point. He was a trooper and my only regret is that it took so long to finish the film and he never got to see it finished – it’s a real shame. And Colleen Heidemann, who plays the batty old neighbour: when I was a child, I had this very sweet old woman with the whitest of white hair called Vivian, who used to live on the estate opposite me. And she had this crazy white hair and she had cataracts so one of her eyes looked quite misty. But she was the sweetest woman and used to babysit me at night and I remember she’d fall asleep in the chair by like seven, and I’d just go through my stepdad’s horror collection of films and put them all on and scare the hell out of myself while this old lady fell asleep. But she was so sweet, so that when I met Colleen and I saw her picture with white hair and I was like, “God, she’s like Vivian”, and I thought, “I need to get in touch with Colleen Heidemann”. And, obviously, she’s a hugely successful model and fascinating woman. I mean, her outlook on life and her energy and her journey in life as well: she really empowered. She’s an older lady, and she’s still dressing how she wants, saying what she wants, getting the cover of magazines – even Vogue – and she’s now the face of an incredibly big makeup brand. She’s doing incredible work, she’s really pushing boundaries. And working with a woman that strong is a really exciting part of filmmaking. I think one of the most exciting things about making films is the characters that you meet, if you’re lucky enough, and she was certainly one of them. And then the kids, Donna and Michael, Page and Keaton, were just truly some of the best child actors we came across. Keaton was so young when we met him and I thought, “How the heck has he not been picked up yet?”. Because Father of Flies was his kind of breakout movie. Yeah, we’re just really lucky with the cast.

Tell us a bit about some of the highlights and challenges of making it – is it true you had to get an exorcism on the set?

That is true! And it wasn’t done for effect. I mean, Americans are superstitious because they’re all nuts. But we were at this house in the woods, and there was something really terrifying about it. And we had some of the interiors built in a set in Tribeca in central New York. And then the house itself that we were shooting in and some of the interiors was in a place called Suffern, and it was on an old Indian burial site in the middle of the woods – it was creepy as heck. Unfortunately, it was vacant because the lady had passed away in there, and I think once we heard that, you manifest these sorts of things. The crew that were there, their imaginations were going wild! And the house I stayed in in New York was terrifying. I had this hire car and I would be the last on set. It was mid-winter, the sun would be down, obviously, I would drive up to this rental house, this knackered old house, at like ten o’clock at night, and I would drive up the driveway and there was this old hut, this broken brick hut on the driveway in front of me. And it had sticks and twigs and everything in it. And a headlight shone into it. And I thought, “God, it would be creepy if there was somebody in there.” Anyway, I went in the back door of this house, it was snowing, as you know, because the film is covered in snow. I went to bed, woke up in the morning, went into the house, went to sleep, woke up in the morning. Then I was upstairs brushing my teeth and looking out on the fresh snow. And during the middle of the night, there are footsteps that must have come out of that building in the snow and walked up to the back door. And I followed the footsteps around the house. Somebody was in that hut when I pulled up! And they came in the middle of the night, walked around the house and up to each window – they were looking into the house as I slept. And then they walked off over the hill. No joke. Hand on my heart. There was somebody in that hut when I pulled up, who walked over the hill. Yeah, that was terrifying. Aside from the terror, it was a really great experience – good fun.

What do you hope that people take away from this film? Obviously, there are the scares and the creepiness, but it’s also tapping into bigger issues about how we deal with trauma, with fears of insanity.

I think that’s what I tried to do. When I wrote the initial script, it wasn’t a horror – I wrote it as an elevated drama, these incredibly emotive scenes and these fears and worries and insanity and villainising the wrong person. And then horror is the structure that sets the tone and – I don’t really want give away too much of the story because there’s people that may have not seen it – but it’s quite obvious, the horror within the story. In terms of what people will take away: I want people to appreciate their families, the people they love. I really do. I want them to second guess before they villainise people – stepmothers aren’t always evil! The mask that we wear doesn’t always reflect exactly who we are inside. And I think that that is the key message of Father of Flies: don’t be too quick to judge and love the people whilst they’re still around, because you never know what’s going to change.

And how does it feel to be putting a film out right now, considering the 18 months we’ve just had?

I made three movies throughout the pandemic, produced two of them and directed one, so I’m just amazed I’ve gone through it. The other ones we’ve had are Quant, the movie on Mary Quant that I produced with Goldfinch, and it’s got four-star reviews. It’s been amazing. That’s so exciting. We’ve got a huge theatrical release with that at the moment and I’ve produced a movie with Kirsty Bell called A Bird Flew In, which is up for awards, from Raindance to the International New Yorker. And then we just found out we won a terrific award, somewhere, which I can’t mention quite yet, so that’s all doing really great. And then we’ve got Father of Flies, which is always the underdog because it’s the horror. I’m just really excited that so far we’ve had some really great reviews, we’ve got a great distribution deal. The more people that see it, the better. When you make any film, there’s always the fear that it will never be finished, let alone throughout the pandemic. So I’m just happy we got to the finishing line. And if five people, if 50 people see it – amazing, you know? It’s a fun film, and I hope people liked it.

What have you got on next? Are you taking a break?

I’m going to direct another movie next year, I think. I’m doing one in Bulgaria, with a lady called Debbie, that’s a similar thing in a way. It’s exploring the ambiguity of good and evil, not villainising people too quickly, not judging. So it’s something I need to explore more! So I’m going to direct that and, as you know, I run production at Goldfinch entertainment, so we’ve got a whole slate of thrillers and horrors that we’re currently putting together, financing and arranging as to how and when will shoot them and who is going to direct what. So it’s exciting times!

Sarah Bradbury

Father of Flies is released on digital download on 11th April 2022.

Watch the trailer for Father of Flies here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS