China’s Hidden Century at the British Museum

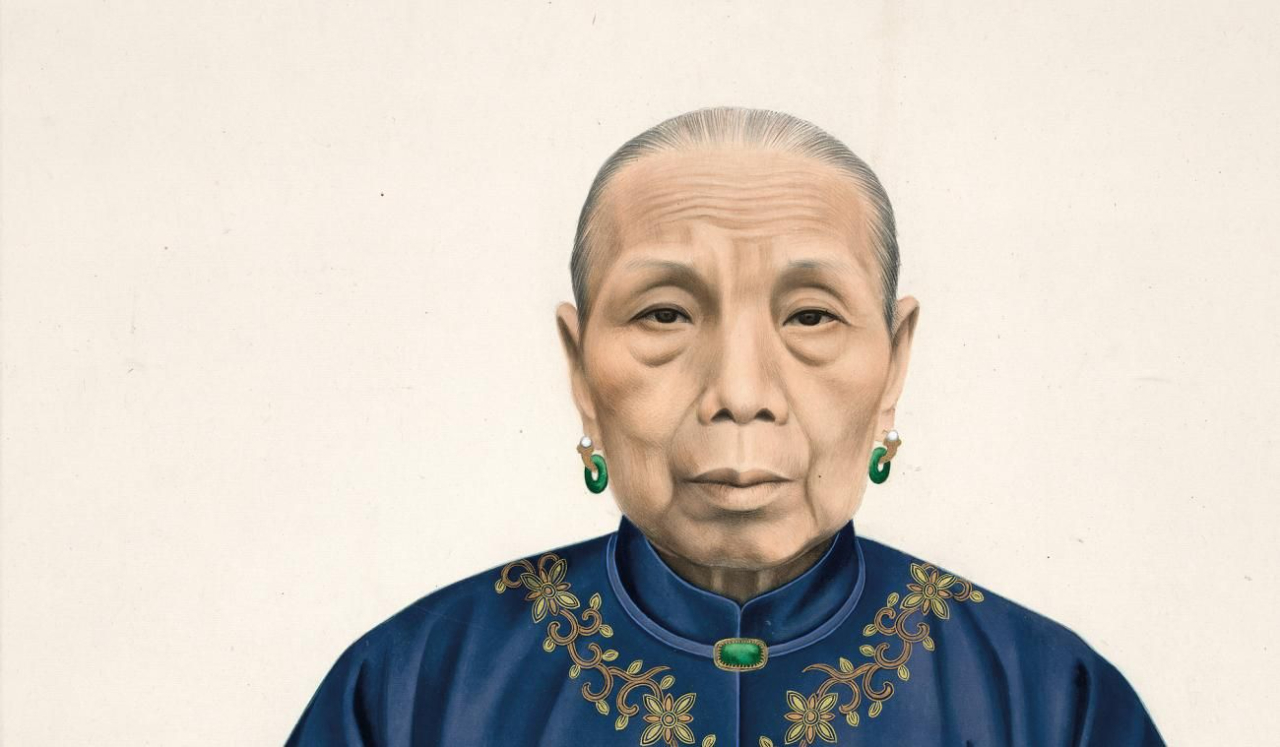

This exhibition covers China’s “long” 19th century, from the accession of the sixth Qing emperor in 1796 to the abdication of the 11th, a boy of five, in 1912, ending 2,000 years of dynastic rule. Qing, meaning bright, was the name assumed by the Manchu warriors who defeated the Ming dynasty in 1644.

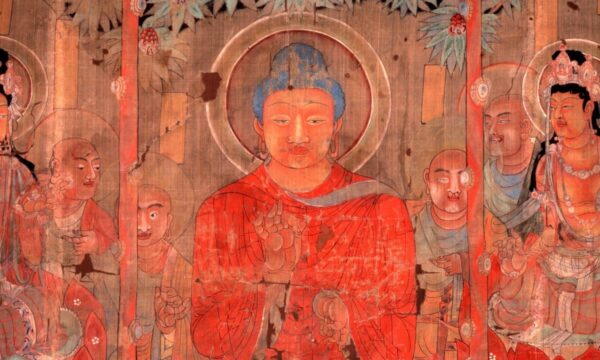

The space is filled with some truly incredible objects. There is a gigantic pair of royal vases, far bigger than a man. A diplomatic gift to King George V on his coronation in 1911, they are decorated with dragons that face each other. They are awe-inspiring, not only in scale but the craftmanship in the cloisonne enamel. There are collections of snuff bottles and archers’ thumb rings (commissioned to provide a snappier release), tiny doll-size women’s shoes that look more like paper boats than anything a human could wear. There is a pipa, a pear-shaped lute, with a bat roosting atop the fretboard. There’s a Buddha in gilt-bronze, his many hands clutching many things, the symbolism of which is unclear to the uninitiated.

There is a still-formidable suit of armour worn by a Bannerman soldier, alongside sketches of military training using terrifying weapons including a trident. There are chunky turquoise glazed stoneware swirls that are remnants from the Summer Palace, destroyed by the British in 1860, who spirited off a Pekinese dog for Queen Victoria’s amusement and named it Looty (yeah, we don’t come out of this exhibition looking well).

There are many incredible items of clothing on display, including a child’s hat that is a mythical fish/dragon designed to scare away evil. A lot of the art and design has moments that look like solemn psychedelia to Western eyes, especially in the fantastical and kinetic depictions of animals, both real and mythical. It could even seem playful if it weren’t for the fact that it shows an ancient and deeply complex belief system that Westerners maybe still don’t have the eyes to truly understand. One of the last exhibits is a flag made after the Qing army was defeated in the Sino-Japanese war in 1895, which acquiesces to the standard rectangular shape other countries used instead of the triangular or square flag previously used by Qing armies. You can’t help but feel that something was lost in this gesture to homogeneity. Why do flags all have to be the same shape?

There is so much going on here that it’s a lot to take in, especially as the exhibits are relatively close together and the space busy. It’s hard to absorb all the different strands that are presented: the military history, the art, the fashion, the everyday items representing an unimaginable number of anonymous lives. A surfeit of ideas and information is no bad thing but, ideally, the collection needed a bigger space to do it justice.

Jessica Wall

China’s Hidden Century is at the British Museum from 18th May until 8th October 2023. For further information visit the exhibition’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS