Black Venus: Reclaiming Black Women in Visual Culture at Somerset House

In 1810, a South African woman named Sarah Baartman was brought to London as a slave and exhibited as a freakshow attraction. Baartman was put on display like an object for the Western male gaze: fetishised, hyper-sexualised and referred to only as the “Hottentot Venus”. Aindrea Emelife first heard this story when she was eight years old and it became the catalyst for her stunning curation of Black Venus, Somerset House’s new exhibition which brings together the works of 18 Black women and non-binary artists to explore, reclaim and challenge the visual narratives of Black women in Western history.

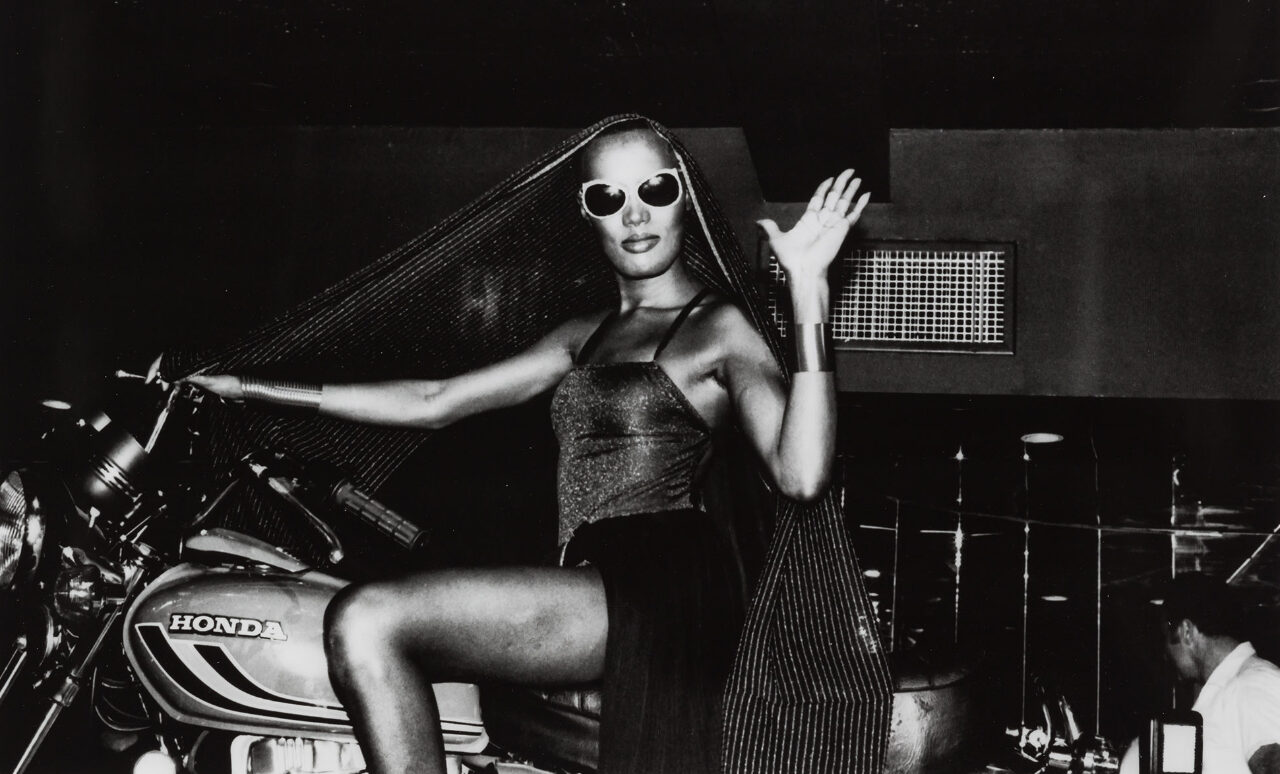

As well as the Hottentot Venus, the exhibition also deconstructs the perceived archetypes of the Sable Venus and the Jezebel, contrasting archival imagery from 1793 to 1930 with 40 contemporary and primarily photographic works, by artists including Carrie Mae Weems, Lorna Simpson, Maud Sulter and Renee Cox.

A particularly impactful piece, which directly speaks to the experience of Baartman, is Renee Cox’s monochromatic self-portrait (1994), which photographs her own body wearing plastic breasts and buttocks, both of which are crudely overexaggerated in size as a reminder of the objectification and sexualisation that Baartman faced. Cox’s body becomes the Hottentot Venus, but here she reclaims her own agency by gazing back at the viewer, in a shift which turns the false body parts into a shining armour that protects Cox. Similarly, Carla Williams’ self-portrait Venus (1992–94) also reclaims the goddess, who, in Williams’ image, is no longer a means of external objectification, but a display of Black beauty, power and sexuality on the artist’s own terms.

Other highlights from the exhibition include selections from Maud Sulter’s 1989 Zabat series, which reclaims the muses of ancient Greek mythology, figures which are typically burdened with Western beauty standards. Sulter puts Black women back into the centre of the frame, both literally, in the centre of the physical gilt frames, and metaphorically, within our cultural institutions.

Equally striking is Lorna Simpson’s Photo Booth installation (2008), which collects 50 portrait photographs from the 1940s, each accompanied by a drawing by Simpson. All of the photographs depict Black men, except for one, which shows a young woman in a dark jacket with her hair pulled back, annotated with a handwritten label, “Marie Adams”.

Overall, the exhibition is an impressive and important affront to the centuries-long horrific objectification and othering of the Black female body. Although this racism cannot be undone, Emelife has curated a space that recognises and reclaims the depth, power and beauty of Black womanhood, acknowledging the complex lived experiences of Black women and breaking down society’s historical and archetypal perceptions.

Eleanor Antoniou

Image: Courtesy of the artist and Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, London

Black Venus: Reclaiming Black Women in Visual Culture is at Somerset House from 20th July until 24th September 2023. For further information visit the exhibition’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS