“I decided to treat myself as someone else – creating the distance between me as a daughter and me as a filmmaker”: Costanza Quatriglio on The Secret Drawer at Berlinale 2024

It must be a daunting task to not only document your family’s own history, but to do so by making a documentary – one that’s unavoidably personal and highly intimate. And there’s also the fact that it has to (in theory anyway) hold an audience’s attention. Using this criteria, director Costanza Quatriglio’s film ticks all the necessary boxes.

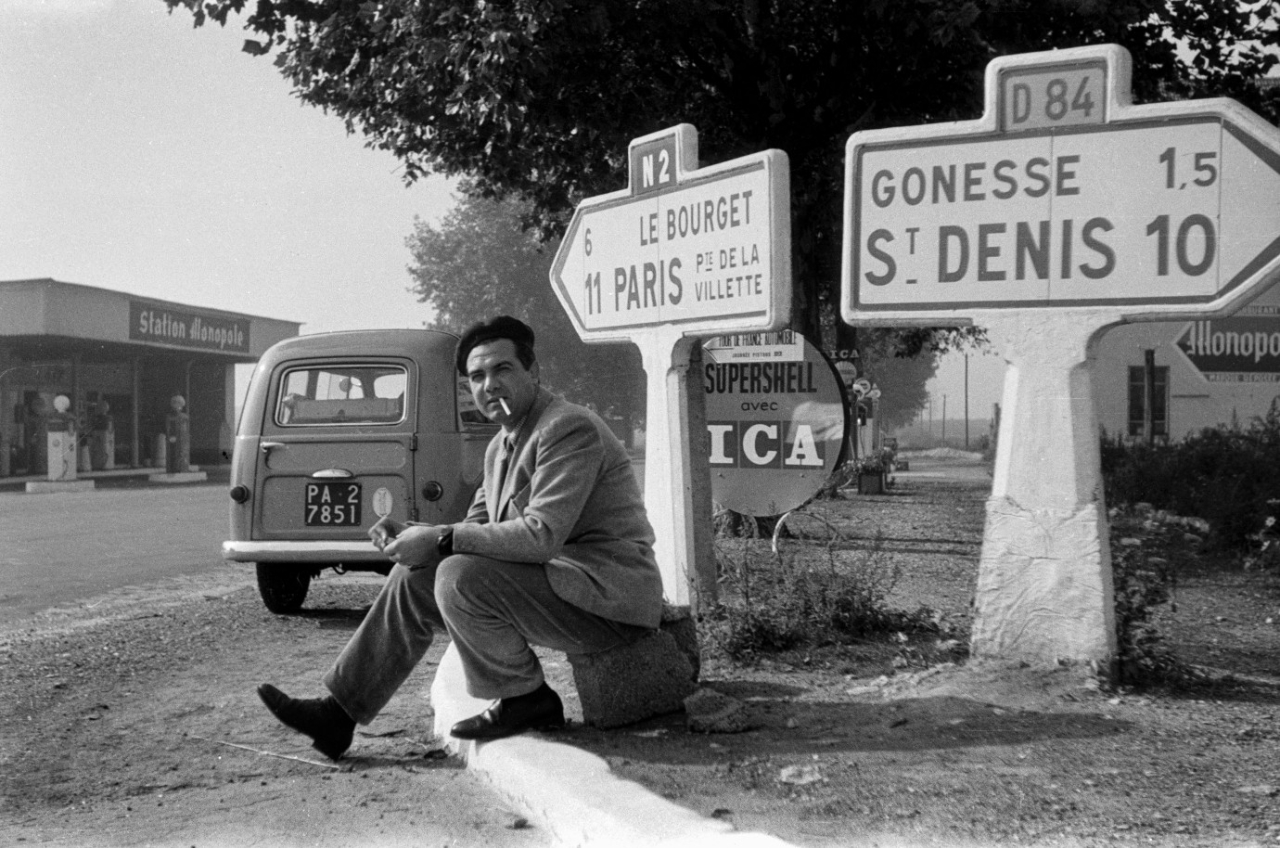

The Secret Drawer details the life and times of the filmmaker’s father, the influential Sicilian journalist and writer Giuseppe Quatriglio. The director has delivered a feature that explores her father’s legacy, her family’s history, and a world going through numerous abrupt changes throughout the 20th century. The film is gentle, warm and wise, and we spoke to Quatriglio as her movie debuted at the 2024 Berlinale.

Early in the film, we see you start the huge task of archiving your father’s work. You mention how you expect the work will be addictive. Was it?

When I was talking about addiction, I was wondering – because every time you open a drawer you’ll find something about the public dimension of my father’s work, and also my private dimension as a person who has grown up in this environment. So it’s like, I want to know more; I want to know more and I find myself like a girl, like a little girl who is discovering herself during the process in the house. So that’s why I’m saying something about addiction, and I want to know more and more and more, because every child has a curiosity to know the life their parents lived before you were born, so it’s very typical and nobody asks and nobody tells, so that’s why I’m talking about addiction. I like that you say gentle, and I thank you, because I wanted to make a process from the relationship between me and my father through the camera, which is the relationship you can see from the footage that I made in 2010, when he was alive – he was almost 90. From that relationship to this relationship, with the absence of him – which is a presence at the same time, so we have we could say absence and presence. Sometimes you don’t know what is present or what is past. That’s why I thought about addiction because I found something about me in the past and then found something about me in the present, because it means a lot for the present, for the time we are in.

You started all the way back in 2010 by recording some footage of your father. Did you know it was going to be a documentary when you started?

No, not at all. I found at the time that it was impossible to meet him, to make the documentary with my father at the time, because I filmed him among his books and documents only to talk with him – and I wanted him to open himself in front of the camera. But it was enough for me at the time, it was okay. But I can confess that I kept all these images, all the footage in my secret drawer, you know because I thought, “Okay, maybe sometime, maybe there will come a day that I will use these images,” but I didn’t know how and when. It happened when I was in the house with the librarians and archivists; they worked with my father’s books and archives, and I felt that as a medium between me and the house, and me and that memory, and I remember that in 2010, I was building the memories of my father – just filming him, and I can say that when I was filming my father in 2010, I was aware that I was building something which will remain. For example, when he used the typewriter (in the film), you see his close up and the images are not really in focus. I remember my emotions when I was filming these images, and I said, “Okay, this is my memory. This is a memory, it’s not real,” it’s just really because I was a daughter, of course, but I am still a filmmaker, and filmmaking is a way to see the world.

You build upon the work of your father, using footage he recorded, and generally make a lot of use of his archives. Do you see the film as being sort of like a collaboration between you and our father?

It was, once. When I watched the film – I finished the editing and everything, just before Berlinale – I watched the film, and I said, “Wow,” I found out that I’m going to combine my sound, for example, with these images and the pictures were silent, of course, without sound, so I put sound on these pictures. It’s like I combine me and him – it’s really strange. Like me, to one person, in the land, which is the land of languages, the land of seeing the world, of watching the world, an interpreter of the world, is not the land of just, “I love you, my father.” No, it’s the land of meaning, it’s the land of how you are in the world, how you stay in the world. It’s strange.

You selected a lot of contemporary music for the film, which is an interesting choice. What did you want to achieve with this music, many tracks of which are cover versions of well-known songs?

I chose to make a journey through these cuts, for example, in the beginning when my father travels (in the documentary), we decided to make a sound like an 80s sound. Elodie Gervaise, who is the singer who collaborated with Giovanni Di Giandomenico, is the composer who felt like an interpreter, like a main character in the movie. In this way, it’s possible to take a journey in the feelings of the film, and I wanted a female voice. I decided to do this because I want to create a funny relationship between the audience and the sound. I didn’t want to be too serious, so I wanted to feel the funny side of this process, which is like life, because this film is like a land where there are a lot of rivers, and you can follow the rivers, and you can go there, and there, and there – you can choose whatever you want, or whatever you like – you feel close to yourself.

Your mother can be seen in the film, but it is primarily about the relationship between a father and daughter. How does your mother fit into the story you want to tell?

For me my mother had a role that was… fundamental, I would say – a very important role for my education for everything and I wanted her to be in the film, but at the same time – she was too important, so important that it would be impossible for me to tell her how important she was for me. In the 2010 footage, she always stayed by the front of the door, not crossing the doorway. How do you say that in English?

Crossing the threshold?

Threshold, yeah. She stayed there because she wanted me to have my own relationship with my father, so I decided to have a short time making the film, but I think it’s intensive. I hope people can understand that she was very, very important to me. At least, growing up, I thought that the role of my mother was more important than the role of my father. Now I understand that they were important in this completely different way, because I felt myself in my brain now similar to my mother, connected to her.

What’s it like to have made such a personal film, and did you feel at all vulnerable during any stage of the process?

It’s strange because I’ve always made films about someone else. I never did something personal, and since now I believe that for me, it would be impossible to do something like that. But at the same time as a narrator, as a documentary director, I understood that while filming at the house, it was necessary to put myself inside the house. That’s why I decided to do this, and I didn’t want to fight with this necessity, so I decided to treat myself as someone else – creating the distance between me as a daughter and me as a filmmaker, and me as someone who is among the books, among the archives, someone who has to be narrated because it was the necessity of the storytelling. So I was like a function for this retelling, and that’s why I accepted to be in the film, otherwise it would be impossible for me.

Oliver Johnston

The Secret Drawer does not have a UK release date yet.

Read more reviews from our Berlin Film Festival 2024 coverage here.

For further information about the event visit the Berlin Film Festival website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS