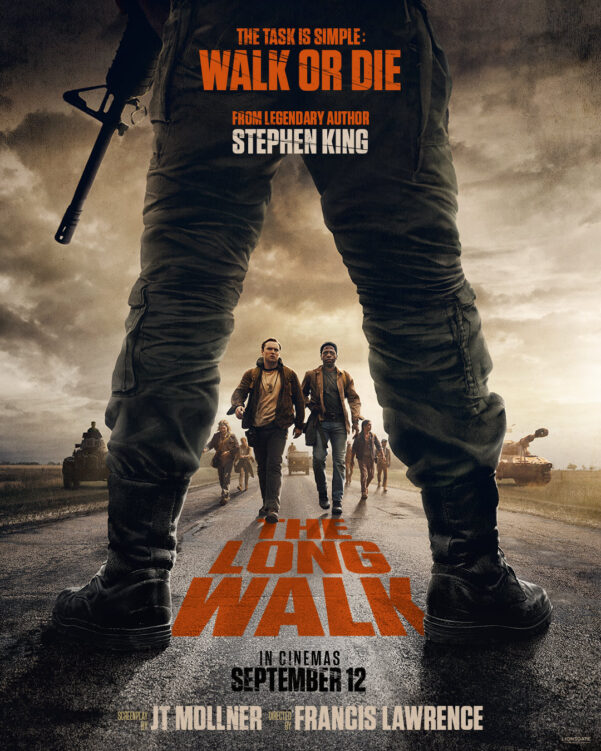

The Long Walk

When anthropologist Margaret Mead was asked about the earliest signs of civilisation, her students expected to learn about the first man-made artefacts, weapons even. Instead, she replied: “a healed human femur.” Because no animal in the wild can survive a broken leg that keeps it from outrunning danger and fending for itself, the idea that this bone had time to heal implies care, community and compassion. The fact that 2025 sees not one but two film adaptations of “Bachman books” (Stephen King’s surlier and more cynical alter ego) speaks to the times we are in, and yet it is the altruism found at the heart of Mead’s anecdote that characterises Francis Lawrence’s The Long Walk.

In this dystopian vision of the United States, once a year, its military regime holds a competition amongst teenage boys to boost morale and the country’s gross national product. 50 contestants – one from each state – partake in a march that in theory spans from the Canadian border of Maine down the East Coast, but de facto ends with the last man standing.

What seems destined for cutthroat rivalry transforms into an achingly beautiful bond among the young men, in particular Ray Garraty (Cooper Hoffman) and Peter McVries (David Jonsson).

Due to its combination of heavy subject matter and visually restricting setup, King’s novel was long deemed unfilmable. This seemed to be proven by the reality that, since its release in 1979, a number of different directors were attached to the story at one point or another, with none of these attempts ever coming to fruition. It now seems like divine dispensation that the filmmaker behind The Hunger Games would be the one to break the curse, since this novel series itself was so clearly inspired by Richard Bachman’s evisceration of America’s hunger for spectacle.

The Long Walk strikes familiar chords to the popular young adult films, but thankfully was only moderately sanitised for a Gen Z audience. The topics of conversation may merely scratch the surface of King’s abysses, but they feel truthful. The dire circumstances of their predicament always catch up on our protagonists – and the viewer – whenever they get too comfortable.

Perhaps because Lawrence has exhausted the idea in his previous work, he is less concerned with the entertainment factor of The Long Walk. In a notable divergence from the novel, he has banned spectators from watching at the side of the road, and its live broadcast to millions of American homes is merely alleged. Instead, he channels all of his rage on the founder of the event: The Major (Mark Hamill in the second of his King double bill this year). A scene, in which McVries encourages Garraty to believe in a family they walk past (ie see the good in people even in moments of despair), perfectly summarises the shift in perspective JT Mollner’s screenplay has taken on. Instead of psychic corrosion and existential unravelling, the movie focuses on themes of integrity in a corrupt world, and presents McVries as a moral anchor.

In the end, it is the combination of a powerful script and splendid casting choices that tie the film together. Where so many other current productions founder at generic and indistinguishable “Instagram faces” of young actors, The Long Walk finally feels like an authentic cross-section of society. Every individual character is vividly drawn and distinct, and in the ensemble’s collective chemistry beats the lifeblood of the feature. If their prior filmographies haven’t already made it obvious, this film firmly establishes Hoffman and Jonsson as the future of cinema.

Selina Sondermann

The Long Walk is released nationwide on 12th September 2025.

Watch the trailer for The Long Walk here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS