Moss and Freud

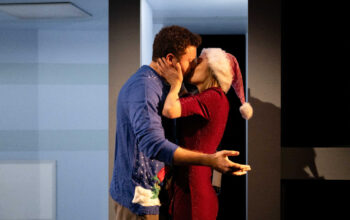

A little complex and very heartfelt, Moss and Freud is a quiet exploration of the fine line between artistic muse and friendship, and the way these relationships blur in the pursuit of art. Less like a biopic of model Kate Moss and her connection with artist Lucian Freud, and more like a story of found family, Moss and Freud tests the boundaries of these frail and varied dynamics, showing there is more than one form of love worth discussing. It stars an alluring performance by Ellie Bamber as Moss and Derek Jacobi’s take on Freud.

The film by James Lucas is one of dissection, specifically surrounding the multifaceted nature of the relationship between Moss and Freud. It’s not just artist and muse – there’s a bit of mentorship and a fatherly nature to Freud regarding his interactions with Moss, but there’s also distance and even a touch of eroticism. The feature creates a hazy disposition in the motivations between the two leads, never truly asserting how each of them sees the other. There are hints of a wider rift, touching on Freud’s complicated relationship with his daughter Bella, who stands as the conduit that brought the two personalities together. The addition of Jefferson and his budding romance with Moss also adds another layer to the artist and his muse’s interplay.

However, where Moss and Freud falters is in its hesitance to delve further into the problematic aspects of its subjects. Their characterisation is diluted, with Moss losing a little bit of the sharp edge that makes her a fascinating figure to follow. While Freud’s abrasive and blunt perspective on art and women becomes a subject of argument between the two, there is no further resolution to its brief mention, and the two rekindle their friendship almost instantly thereafter. It’s this anxiety to dive further into these thorny matters, including their age gap, that holds the movie back from truly taking off.

There’s intrigue in how Moss’s party lifestyle is portrayed, full of glitter and sharp camera flashes. Archival-styled footage is spliced in between to further her glamour and spiral. This is done well to contrast against the quiet calm present in the weekly visits of three evenings that Moss spends with Freud. Their lives instead are filled with sly laughter and mischief at the dinner table, and the focused silence when he’s painting her. The clash between these different worlds is most especially prominent during Moss’s 30th birthday, where Freud awkwardly sits in the middle of a crowded and loud party – eyes lingering on Moss’s disappearing body, presuming her to have gone to do drugs. What follows is an argument between the two, highlighting how Freud doesn’t fit this world that Moss lives outside of their nights together.

Aesthetically, the picture lacks flair and colour. It’s disappointing that Moss and Freud, set in the 2000s – famously known for its vibrant fashion and neon-drenched parties – are rendered desaturated and cinematically dull. For a piece exploring one of the most influential models of all time, and an acclaimed artist, it’s a lacklustre visual experience for viewers.

Whether or not this is an honest retelling of the relationship between their real-life counterparts, there is something pleasant and heartwarming in following the journey these two characters go through in their self-discovery and friendship. Beyond some of the interesting layers of Moss and Freud’s relationship, the feature doesn’t accelerate into a more cinematic experience, nor does it delve deep enough into both individuals to truly capture any exhilarating character arcs. Moss and Freud is overall safe but emotionally touching nonetheless.

Mae Trumata

Moss and Freud does not have a release date yet.

Read more reviews from our London Film Festival coverage here.

For further information about the event visit the London Film Festival website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS