Turner and Constable: Rivals and Originals at Tate Britain

JMW Turner (1775-1851) and John Constable (1776-1837) have long been treated as the Ali versus Frazier of British Art: the former commonly portrayed as the pugnacious, pioneering genius, the latter, the industrious pragmatist. Turner, whose father was a Covent Garden wig maker, was heralded as a prodigious talent from an early age, attending the “discourses” lectures of Sir Joshua Reynolds at the Royal Academy. For all of his unquestionable ability, Constable, the son of a wealthy Suffolk mill owner, was an altogether slower burner. This year marks the 250th anniversary of the births of these titans of British art, with Tate Britain seizing the chance to chart their “entwined lives and legacies” in a major combined exhibition entitled Turner & Constable: Rivals and Originals.

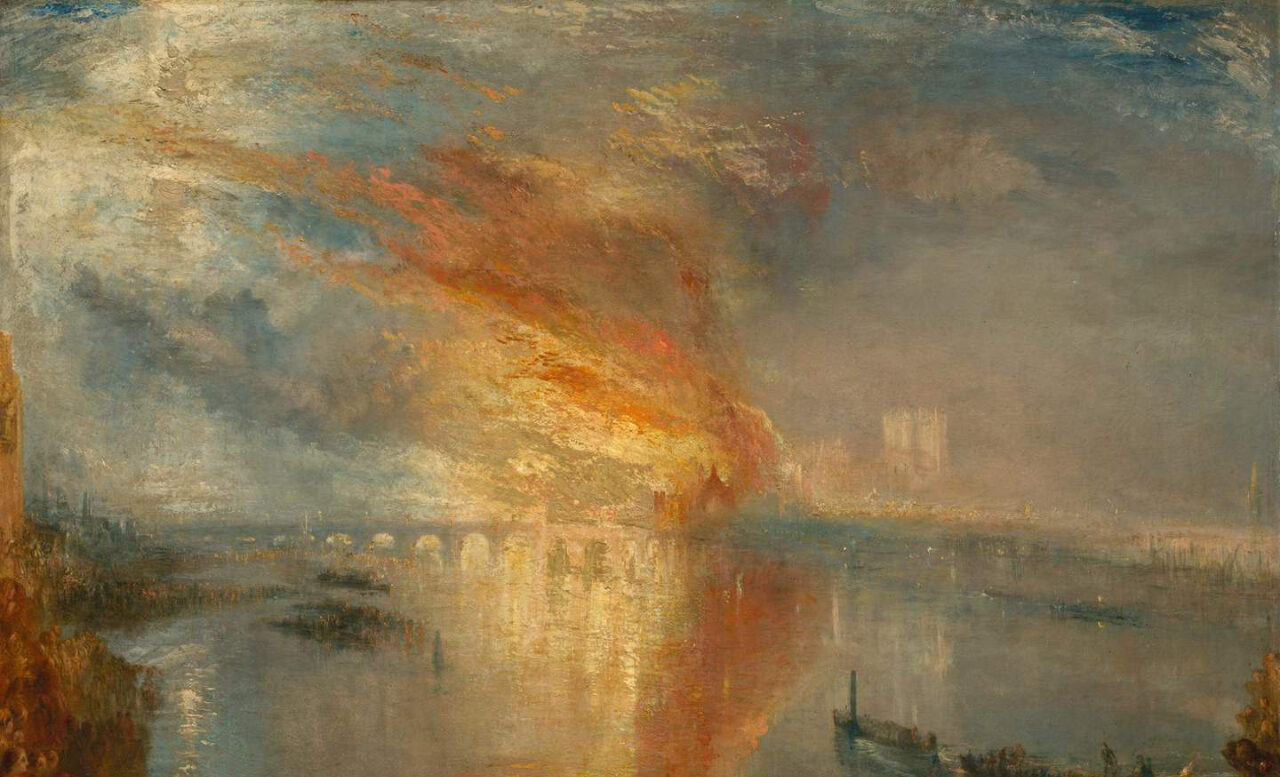

Tate has unquestionably gone for the proverbial juggler, throwing virtually everything into the mix with 196 works on display, 95 of which are from their own collection. The Fighting Temeraire and The Haywain are noticeable in their absence, but there’s more than enough to quench the taste buds without them. Constable’s first six-footer, The White Horse (1819), on loan from the Frick across the pond, is viewable in the UK for the first time in over 20 years. Another work unseen in these shores since 1883, Turner’s painting of the former Houses of Parliament ablaze in The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons, 16 October 1834 (1834) sears its way into the retina.

A walled timeline in the opening room really underscores how much sooner Turner was able to gain recognition. Entering the Royal Academy at 14, by the age of 27, he had become elected a full academician, an honour not bestowed upon Constable until he was 52. The Suffolk native would only receive his first mention in the press at 31. Differing in temperaments but close in age, much has been made of their rivalry both during and after their lifetimes, with the critic Edward Dubois – quoted here – referring to them as “fire and water”. Turner’s legendary upstaging act when he added a red buoy to his seascape, Helvoetsluys: The City of Utrecht, 645, Going to Sea (1832), just as Constable was varnishing The opening of Waterloo Bridge at the 1832 RA annual exhibition, is naturally mentioned here. Rather than securing the former from its current Japanese home, Tate has opted to show a clip of the incident portrayed in the 2014 film Mr Turner, with Timothy Spall playing the title role. Constable’s Waterloo Bridge work, on which he laboured for 13 years, is featured here; however, the artist’s scarlet-flecked Thames scene clearly prompts Turner’s concern at the prospect of his cool-toned seascape making less of an impact. Interestingly, Tate curator Amy Concannon has made the decision to lay more emphasis upon another historic episode. When invited to hang the annual Summer Exhibition in 1831, Constable incurred the wrath of his famous compatriot by ensuring his dramatic work, Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows (1829-31), was hung next to Turner’s similarly large Caligula’s Palace and Bridge (1831). Now those jousting works are reunited.

Encompassing 12 rooms and essentially arranged chronologically, Rivals and Originals reveals both men elevating British landscape painting to new heights. It’s intriguing to see Turner and Constable’s careers juxtaposed alongside each other. In many ways, they are opposites: Turner searching for meaning in the universal and the sublime, Constable in his beloved Suffolk landscape. The Londoner was by far the more travelled of the two men, his sketchbooks testifying to his particular exploration of the light and historical sites of Italy, Switzerland and France. Bewitchingly, vivid sketchbooks belonging to both artists offer telling insight into their working approaches throughout this show. Also on display are other possessions: paintboxes, oil paint-covered palettes, joined by Constable’s surprisingly diminutive folding sketching chair and even Turner’s fishing rod and reel. There’s something very elegant about Constable’s beautifully inscribed entry ticket for an RA lecture, a far cry from modern times.

Turner certainly had a taste for the grandeur of classical landscape. His travels, be they across mainland Europe or Britain, provided him with the visual stimulus to create works of universal significance. Throughout, one finds him drawing on the awesome power of nature to generate the dramatic effect of his narrative, a clear case in point being Snow Storm: Hannibal and his Army Crossing the Alps (1812). On display at Tate, the epic painting finds the legendary enemy of Rome and his Carthaginian army’s ambition to attack their hated foe thwarted by a violent snowstorm in the Alps. Perhaps the artist is using the archaic event as a metaphor to Napoleon’s disastrous invasion of Russia, which took place the same year of its completion. Like with Turner’s famous late work of a stricken steamship in peril, the storm’s terrifying vortex dominates the composition, relegating Hannibal and his army to distinctly minor positions. The Londoner’s mature phase sees him conjuring up the visionary works that would so stir the French Impressionists in future decades. Light and Colour (Goethe’s Theory) – The Morning after the Deluge – Moses Writing the Book of Genesis (1843) is palpably a love note to the sublime beauty of light and air. Expressibly depicting Moses at work on the opening chapter of the Bible, the prophet is almost indistinguishable from the sky. Turner gives far greater pictorial importance to the swirling mass of yellow, engendering a sense of the sun shining in the aftermath of the Flood, signifying spiritual rebirth and creation. Channelling Goethe’s theory on Light and Colour, published in 1810, the artist produces atmospheric effects with a vibrant palette, prioritising intense emotional experiences over realistic scenes.

Critics, with John Ruskin numbered amongst them, have often had a tendency to regard John Constable as a relatively conventional figure when compared to Turner, his contemporary. It is undeniably true that the son of a mill owner found constant inspiration from his particular part of rural Suffolk, his deep connection with his surroundings giving rise to works such as Flatford Mill from the Lock (1812). However, as the current exhibition increasingly bears out, the ostensibly prosaic nature of his settings should not be confused with a lack of artistic vision or originality. Close inspection of his canvases on display reveals his radical mark-making, quite at odds with the smooth application favoured by more conservative artists at the time. Interestingly, Amy Concannon holds the view that Constable showed an inclination towards technical innovation earlier than his great rival. Many of Constable’s sketches on show have an amazing immediacy: a clear example being his stunning pencil drawing Fir Trees at Hampstead (c. 1833) and Rainstorm over the Sea (1828). Created in Brighton when the artist was visiting his tuberculosis-suffering wife, the latter’s flurry of black clouds carries a terrible sense of foreboding as well as offering more evidence of his expressiveness.

Constable’s remarkable cloud studies from earlier in the 1820s prove terrifically spontaneous evocations of the skies above us two centuries ago. Late period canvases like On the River Stour (1834) frequently see the artist using his palette knife to apply oil paint densely into the image; those characteristic white streaks of his are an almost savage act of abstraction. Exhibition organisers have sought to identify similarities between the artists: both men surprisingly received no training in oil painting during their RA education, forcing them to learn from scratch. On occasions, Constable’s sketches, such as Rainstorm over the Sea, resemble the hand of Turner, but generally speaking, paintings by the respective greats prove far easier to distinguish.

Destined to be forever pitted against each other by the gods of art history, Turner and Constable continue to impact upon subsequent generations as the years rumble on. Tate brings this epic saga to a close with a short new film featuring eminent contemporary artists: Bridget Riley, Frank Bowling, George Shaw and Emma Stibbon offering their thoughts on the respective legacies of both men. Compelling, myth-busting, frequently awe-inspiring, this clash of the best of British reinforces Turner’s radicalism whilst simultaneously making a mockery of claims that Constable was a mere sentimental, one-dimensional capturer of a lost rural idyll. This is a tremendous show, not to be missed.

James White

Photos:

Turner and Constable: Rivals and Originals is at Tate Britain from 27th November 2025 until 12th April 2026. For further information or to book, visit the exhibition’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS