& Sons

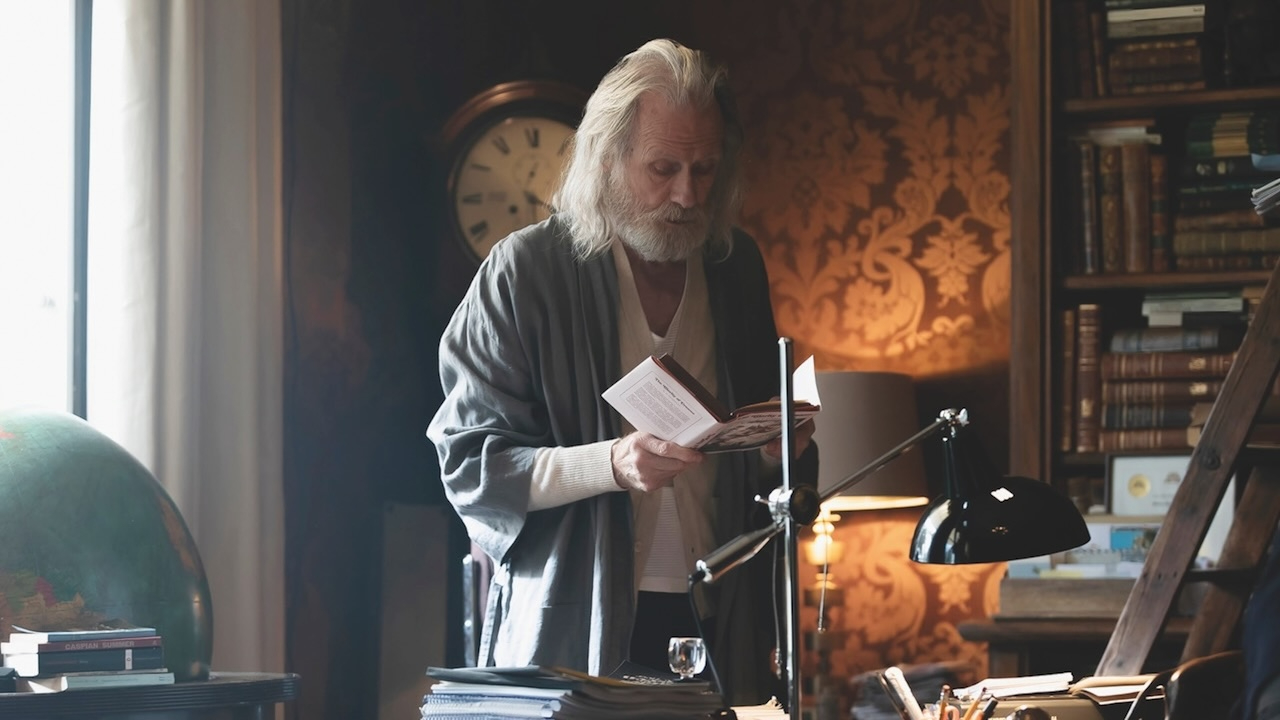

In Bill Nighy’s long and illustrious career, the soused, washed-up crooner Billy Mack in Love Actually looms large, along with the wisdom he resolved to dispense to the youth. “Don’t buy drugs”, he solemnly intoned on daytime TV. “Become a popstar and they give you them for free!” Seeing Nighy in Argentinian filmmaker Pablo Trapero’s English-language debut, it’s tempting to imagine that one is watching the very same character at the logical conclusion of his excesses. Instead, the actor here essays another distinct type: the reclusive, half-mad novelist drowning in booze, regret, and a trail of decimated familial relationships.

Holed up in a secluded country estate and resembling an undernourished Santa Claus, AN Dyer has transferred what little hope remains to him onto the youngest of his progeny, the college-bound Andy (Noah Jupe), who could not be more desperate to get away from the old man. Suspecting the Grim Reaper will soon come a-calling, Dyer calls on his two estranged adult sons (Johnny Flynn and George Mackay, respectively) for an emergency meeting, hoping they will care for the young lad in his inevitable absence. As set-ups go, so far, so familiar. One may be tempted to think of Gene Hackman’s crotchety patriarch lying and scheming back into his family’s hearts in The Royal Tenenbaums, or the torment of the adult children of a mediocre artist and far worse parent at death’s door in Noah Baumbach’s The Meyerowitz Stories. When taking stock of the film’s co-screenwriter Sarah Polley, one may even cast one’s mind to her own brilliant, searching documentary (2012’s Stories We Tell) on the long-term familial effects of two very different artistically inclined parents, and one may further contemplate how unfortunate it is that this newer movie largely puts one in mind of other, more fully realised ones.

It is wholly to the credit of Polley, Trapero and, presumably, David Gilbert’s source novel that through this tired-seeming set-up, & Sons has had a doozy of a spanner waiting to be thrown into the works. When the reveal comes, it proves unexpected enough – and unhinged enough – to re-invigorate the whole enterprise, and to remain worthy of going unspoiled. All one need say is that suddenly, all the usual reproachments and long-held petty grievances we’ve come to expect are charged with a newfound absurdity, turning compulsively watchable what may otherwise have been staid. One only wishes the film itself seemed to realise and revel in the madness as much as you, the viewer, may.

Alas, Polley’s script remains most comfortable in the realm of grand melodrama, the kind where exposition is helpfully doled out in flat, declamatory sentences along the lines of, “You had an affair, which devastated mother and led to the birth of a child who is Andy!” It’s not that & Sons is unaware of the potential for scathing comedy embedded in its premise; there are many a time when Flynn and Mackay’s exasperated heirs find that laughing is all they can do. Still, the feature remains stubbornly resistant to humour, even when it stumbles into being rather funny despite itself. It’s there in Nighy trashing his haunted old house to operatic scoring, taking the time out of his fit of passion to carefully open the window so that a chair might be thrown out of it. It presents itself yet again when revelations that are just as earth-shattering for all of mankind as they are for this one family (there is no jest here) are ignored in favour of old grudges over who plagiarised who. There is such wailing and gnashing of teeth in the homestretch (not least from a never hammier Nighy) that one suspects it would reach the sublime were it simply 10% funnier, just that little bit more willing to acknowledge and take in stride the grandiose silliness of it all. Nonetheless, one walks away with the faintly invigorated sense of something reaching to transcend its set-up’s dreary parameters to achieve something bigger, grander and, yes, a little sillier.

Overall, despite the valiant efforts of its cast (with particular credit due to the weathered dignity Imelda Staunton brings as Dyer’s long-suffering ex), no amount of theatrics can make & Sons’ human drama more tangibly affecting. Still, the movie is never less than watchable, in large part due to a genuinely gobsmacking twist that leaves the whole film charged with newfound, unpredictable energy. In a sea of indistinct family dramas, here is one that boldly takes a stand against boredom, even if its sombre ambition betrays its greater potential for satire.

Thomas Messner

& Sons does not have a release date yet.

Read more reviews from our London Film Festival coverage here.

For further information about the event, visit the London Film Festival website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS