“Wuthering Heights”

A man gasps for air. He moans, grunts. Is he pleasuring himself? Gotcha! He is being hanged in the village square. And yes, he has an erection. This spectacle sends the townspeople into a kind of ecstatic and uninhibited celebration, where adults couple in the mud, heedless of who is watching. Thus begins Emerald Fennell’s “Wuthering Heights”, quotation marks insisted upon by the director, who has said this is the version she remembers reading at 14. It arrives as a Valentine’s Day offering, advertised as the greatest love story of all time. At this critic’s screening, viewers were handed cards that read, “So kiss me again and let us both be damned,” plus a complementary packet of tissues. For tears, presumably.

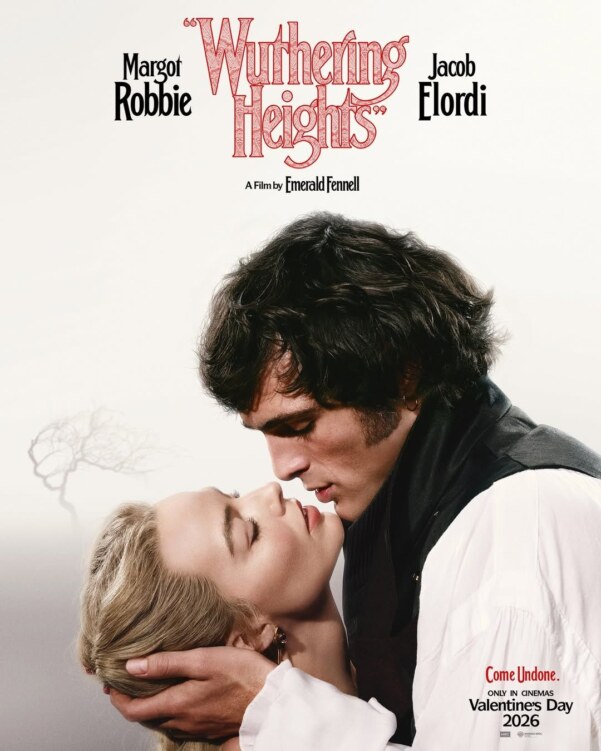

Only the first half of Brontë’s 1847 novel survives the adaptation, and much of that has been thinned down. Secondary figures are minimised or removed entirely, to leave only exposed the central blaze of Cathy and Heathcliff. In the novel, Brontë pairs a bony Yorkshire girl with brown ringlets and a dark-skinned gipsy of ambiguous origins. Fennell casts movie stars Margot Robbie and Jacob Elordi, both white Australians. Robbie, at 35, plays Cathy as a feral coquette with immaculate teeth. Elordi’s Heathcliff is tall, sculpted, and camera-ready even when smeared with mud and horse sh*t. The raw, awkward adolescence of Brontë’s lovers is replaced by glossy magnetism.

Brontë’s Heathcliff is formed by humiliation. His cruelty is specific and retaliatory, sharpened by Hindley Earnshaw’s abuse and by the class system that excludes him. Fennell eliminates Hindley and transfers the household’s violence to Cathy’s father, Mr Earnshaw (played brilliantly by Martin Clunes), here an alcoholic tyrant who brutalises everyone within reach. Elordi’s Heathcliff becomes something else: a soaked romantic martyr. He is almost always wet, standing in the rain, warming Cathy, staring through the mist. After overhearing Cathy consider Edgar Linton’s proposal, he disappears for five years and returns rich, mysterious, and with a better haircut. In the novel, this reappearance carries the force of a long, calculated revenge. Here, it feels closer to a makeover reveal.

Visually, the feature is at its most persuasive, with cinematography by Linus Sandgren. Fennell divides Yorkshire into two realms. The Wuthering Heights farmhouse is rendered in mud, blood and shadow. The Lintons’ home looks almost edible, awash in saturated colour and surreal detail: strawberries the size of cabbages, walls that resemble flushed skin. Brontë’s moors, which in the novel inspire both delirium and revelation, are reimagined as a kind of psychedelic runway, with skies a dense, artificial red. Jacqueline Durran’s costumes lean into fairy tale, all red cloaks, silver gowns, milkmaid corsets, and jewelled crosses. None of it is historically plausible, but it’s undeniably striking.

Yet the beauty of the movie cannot disguise an emptiness at the centre. The story boils down to a single, swinging question: Will Cathy and Heathcliff get together or not? To keep things interesting, Fennell adds a heavy dose of provocation. Joseph (Ewan Mitchell), once an elderly and unsympathetic servant, becomes a cute farm boy with a taste for BDSM. Isabella Linton, naive and proper in the novel, is recast as a smirking eccentric who marries Heathcliff as an enthusiastic submissive, later appearing chained and barking like a dog (Alison Oliver is hilarious in this role). But in the end, the moments that make us laugh or squirm feel entirely ornamental. They don’t deepen Brontë’s world so much as poke it with a stick.

Ultimately, “Wuthering Heights” plays like a lush, sometimes very sexy showcase of Cathy and Heathcliff circling each other, then finally giving in. When they do, they seem to consummate their passion everywhere: in the grass, in the bedroom, in a carriage, against a garden wall. The montage goes on. And on. Robbie and Elordi have real chemistry, assisted by gauzy light, artificial sweat, and Charli XCX’s amazingly sultry, vaporous soundtrack. Yet no amount of face-licking, finger-sucking, or barn humping can quite summon the wild, punitive grandeur of Brontë’s imagination. In the novel, Cathy and Heathcliff’s bond feels metaphysical, destructive, almost demonic. Here, it is passionate, photogenic, and curiously safe. The movie insists on its own intensity. Brontë never had to.

Constance Ayrton

Wuthering Heights is released nationwide on 14th February 2026.

Watch the trailer for Wuthering Heights here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS